India-Czech

India and Czech Republic: Exploring Ancient Connections and New Horizons

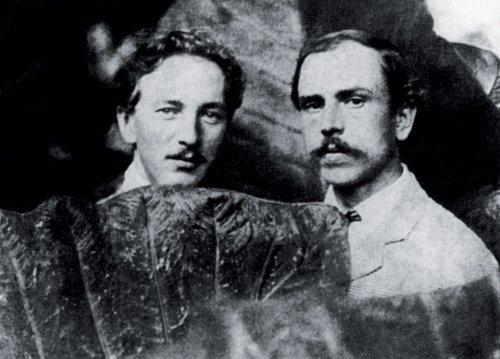

How did Rabindranath Tagore shape cultural and intellectual ties between India and Czech Republic?

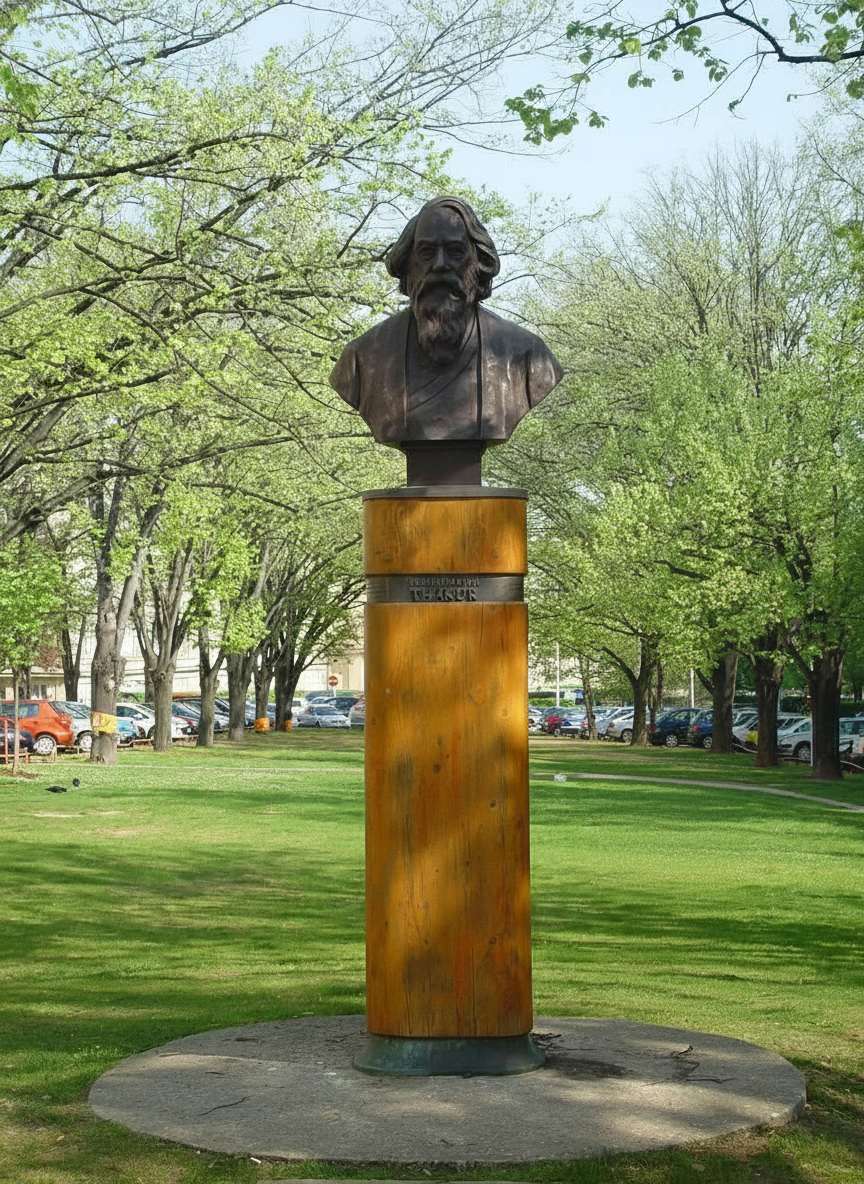

By temperament and practice, Rabindranath Tagore was a bridge-builder: not the brittle, parliamentary kind of diplomat but a public intellectual whose poems, plays and ideas traveled as petitions for humane education and cross-cultural sympathy. In Prague his presence took visible form — a street named Thákurova, a bronze bust, two visits in the 1920s, and a string of translations and performances — and, less visibly, it left a philosophical trace in Czech letters and pedagogy. Numerous radio features, archival reportage and scholarly essays on Tagore’s educational thought — show how a poet from Santiniketan became a recurring interlocutor for Czech scholars (and, through them, Czech audiences) during an era marked by political turbulence and a hunger for humane alternatives to dogma. Tagore’s visits to Prague were short but consequential. He came in 1921 (a brief lecture tour) and again in 1928; the latter visit saw two of his plays staged at the National Theatre, and in the German theatre. These theatricals brought his dramatic voice into Czech public life and prompted musical responses (Leoš Janáček, for example, set Tagore’s words into choral music). These concrete cultural events — lectures in the Lucerna ballroom, plays on the National Theatre stage — are the kind of archival waypoints that explain why Tagore’s name persisted in Czech cultural memory. If one asks why Tagore mattered to Czech intellectuals, the answer given repeatedly in the Czech sources is humanism in multiple registers: literary humanism (the lyric optimism of Gitanjali), pedagogical humanism (an education centred on freedom, nature and creative activity), and political humanism (a public stance against fascism and for international solidarity). Czech scholars point to the affinity felt since the nineteenth-century national revival — an early interest in Sanskrit and a romantic sympathy for colonised nations — and to institutional friendships that turned into personal ones (Vincenc Lesný, a founder of Indology at Charles University, became a close friend and interlocutor; Dušan Zbavitel later became the country’s foremost Tagore scholar and translator). These details are important: they make Tagore’s Prague presence less an exotic import and more a reciprocal intellectual conversation. Tagore’s educational thought provides another archival anchor for Czech admiration. His project at Shantiniketan and its later institutionalisation in Visva-Bharati embodied a pedagogy that fused naturalism, idealism and internationalism. It included methodologies such as learning in the open air, instruction in the mother-tongue, arts integrated into the curriculum, and a method that privileged activity, dialogue and self-discipline over rote memorisation. Contemporary Indian academic surveys of Tagore’s pedagogy emphasise these features — self-realisation as an aim, the role of the teacher as a guide not taskmaster, and a curriculum that tied local culture to global exchange — and they explicitly cast Visva-Bharati as a meeting place for scholars from many lands. It is precisely this blend of the local and the universal that Czech academics and cultural figures found congenial. Tagore’s humanism also carried political weight. In the 1930s, he publicly condemned fascism and supported democratic solidarity with Czechoslovakia; his gestures were read and re-read on both sides, thereby cementing his image in Czech memory as an “ambassador of peace and understanding.” That moral voice mattered greatly at a time when Prague’s civic life was being thrown apart by extremism. Tagore’s public interventions, and Czech responses (Karel Čapek’s broadcast greeting in 1937, for example), became part of a shared archive of resistance to tyranny. These episodes — public letters, broadcasts and gestures of solidarity — are not mere ornaments in the story but evidence of how ethical ideas were converted into civic practice. Two institutional mechanisms explain how ideas moved across this bridge. First was the personal and scholarly network, such as that with Vincenc Lesný, who was not only an early Czech Indologist, but he was also invited as a teacher at Visva-Bharati, and it was Lesný’s friendship that helped in procuring Tagore’s Prague invitations and getting Czech translations done of his work. Second was the steady work of the translators and publishers — Dušan Zbavitel’s translations and the republication of Tagore's work in the 1950s — kept Tagore’s voice audible even through ideological shifts in postwar Czechoslovakia. Taken together, these mechanisms produced a many pronged reception: Czech composers set Tagore’s lines to music; Czech theatres staged his plays; and Czech scholarship debated his pedagogy and philosophy. For readers interested in what Tagore taught by example, his institutional footprints are instructive. His creations, Shantiniketan and Visva-Bharati, embody a pedagogy of openness — to include learning through nature and craft, instruction in the mother tongue, and an insistence that education serve the entire life of a student, rather than being treated merely as a preparation for exams. These features have been well documented in Indian institutional surveys and contemporary essays on Tagore’s educational theory. These practical commitments explain why Czech academicians, themselves interested in humane education and comparative philology, were attracted to and stimulated by Tagore’s work.Finally, a short note about intellectual kinship: several of the available essays that situate Tagore in a broader frame connect his humanism to other modern Indian figures. Scholarly overviews identify Tagore and Gandhi as modern humanists — differing in practice but overlapping in a commitment to human dignity and anti-colonial ethics — and such comparisons help place Tagore within a wider modern Indian formation that resonated with Czech hopes for humane politics and pedagogy.Regarding Tagore's connection with, and visits to the Czech Republic, what survives most prominently in the Prague archives is not merely a catalogue of events, but a bouquet of civic learning: a poet’s lectures, a friend-scholar’s translations, a composer’s choral settings, theatrical stagings, and a stream of public letters and broadcasts that together demonstrate how ideas travel. Tagore’s legacy in this dialogue is double: in India he left an institutional model (Visva-Bharati, Shantiniketan) that insisted on pedagogy as a form of freedom; in Prague he left an ethical script that writers, musicians and scholars could read as an alternative to authoritarian certainties. That two-way conversation — pedagogical, musical, theatrical and political — is the historical fact the sources keep returning us to. Sources:https://tinyurl.com/25kac82u https://tinyurl.com/29juycnp https://tinyurl.com/297exbpl https://tinyurl.com/23vgan6u https://tinyurl.com/24dgxebt https://tinyurl.com/2cml9tvr https://tinyurl.com/mr3k2zukMain Image: Thakurova Street in Prague is named after Rabindranath Tagore

From Purkyně’s Microscope to Today: How Czech Precision Meets Indian Scale in Neuroscience

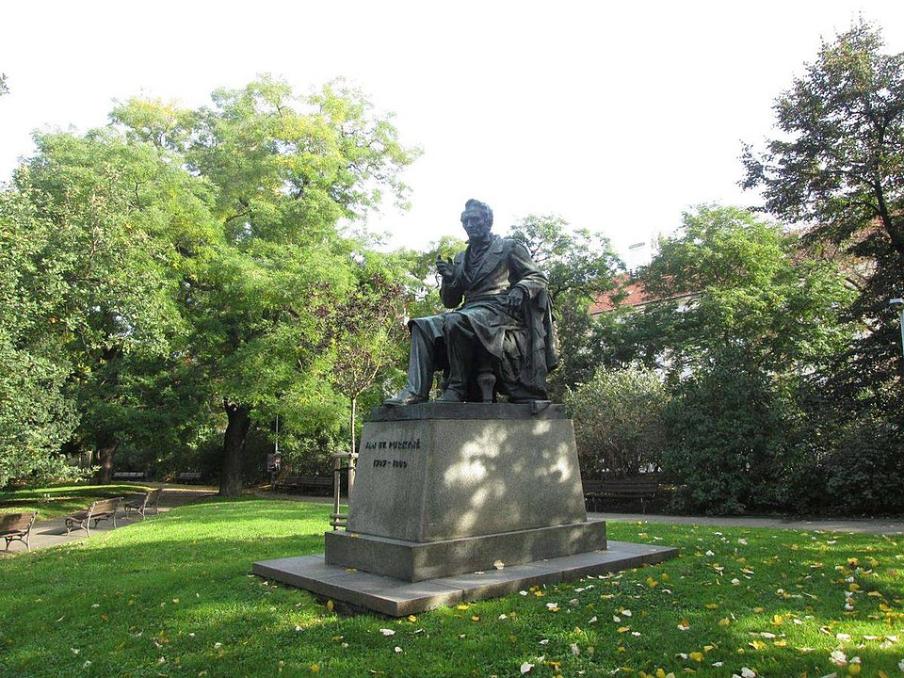

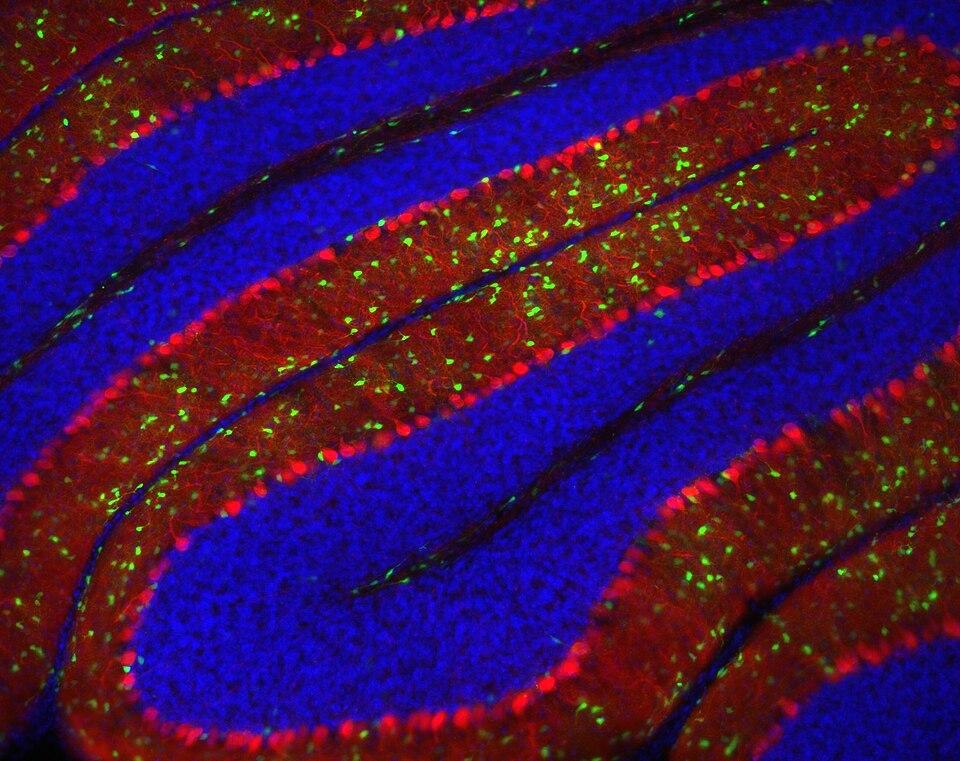

In the quiet light of a nineteenth-century laboratory Jan Evangelista Purkyně sketched neurons whose forms would reverberate across two centuries of biology. The Purkinje cell — a single, striking neuron with an enormous, plate-like dendritic tree — was first described by Purkyně in 1837 and named after him. It remains one of the most emblematic cells in the brain, a compact lesson in how structure and function entwine. Purkyně’s work was not merely descriptive: his careful staining, patient observation and insistence on method established a template for cellular physiology that later generations would refine with optics, electrophysiology and molecular tools.The Purkinje neuron still matters because its architecture makes it a sensitive reporter of disease. As a principal inhibitory output of the cerebellar cortex, its survival and synaptic integrity influence motor control, learning and the fine balance of brain circuits — domains implicated across a range of neurodegenerative conditions. In short, the careful focus Purkyně applied to single neurons continues to pay dividends. Modern scientists watch Purkinje cells to learn how networks fail in disease, and how they might be coaxed back to health.Czech science, rooted in that tradition of exact observation, has not rested on its laurels. In recent years Czech laboratories reported a method that lets investigators damage cells at a very small scale and then watch, in real time, the cell’s immediate reaction to that injury — a sort of controlled, microscopic wound and an equally precise readout of how the cell copes. The team behind this work describes creating a tiny burn or blister on or inside a cell and recording the cascade that follows; the approach promises to reveal molecular and biophysical steps that underlie neurodegeneration and to test interventions aimed at halting or reversing cell death. It is a continuation of Purkyně’s ethos — refined now with lasers, live imaging and molecular sensors.If Czech labs supply methods and mechanistic insight, India brings institutional scale and a focus on translation. The Council of Scientific & Industrial Research and its family of laboratories — and related centres such as the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB) and the National Brain Research Centre (NBRC) — provide the platforms for moving cellular discoveries toward therapy. CCMB’s molecular toolsets and NBRC’s focus on brain research and neuroinformatics create a pipeline that ranges from cultured neurons and genetic assays to computational models and preclinical testing: the kind of end-to-end capacity that turns a mechanistic insight into a therapeutic question.This complementary architecture is not accidental. India’s research ecosystem prioritizes translational pipelines — repositories, imaging suites, animal models and clinical linkages — while Czech science often focuses on high-precision methods and conceptual breakthroughs. That complementarity shows up in practical ways: a Czech method that maps subcellular responses provides hypotheses and assays that Indian labs can deploy on larger sample sets or human-derived cells; conversely, Indian clinical and translational expertise helps frame which cellular readouts are most relevant for therapy. Together they close the loop between what is possible in a single cell and what is necessary for a patient.Policy, meanwhile, is catching up with practice. A joint statement on innovation between India and the Czech Republic names health, biotechnology and researcher mobility as priority areas — a diplomatic framework that encourages exchanges, joint projects and shared funding mechanisms. Under such agreements, protocols can be harmonised, data can be shared responsibly, and young scientists can move across laboratories to learn complementary methods. Where once ideas might have travelled as isolated publications, today institutional pathways exist to carry methods, samples and expertise from Prague to Hyderabad and back.Education and institutional culture matter too. Czech universities and institutes honor their past while engaging the future — tributes to Czech scientists are paired with new collaborations and open-door programmes that include Indian partners; such ties are not merely ceremonial but functional, creating pathways for student exchange and joint workshops where classical histology meets modern imaging. The result is a new generation trained to read dendritic arbors and to apply laser-based perturbations, to respect the history of discovery even as they build tools to fix what goes wrong.Taken together the story is simple and practical. One nation’s centuries-old attention to cellular detail produces methods that reveal how single cells fail; the other’s institutional breadth offers routes to test, validate and translate those findings. Purkyně’s microscope and the modern laser are part of the same intellectual lineage — a lineage that today moves across borders through formal partnerships and informal collaborations. If the goal is therapies for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and related disorders, the pathway runs from a damaged cell on a Prague slide to traction in Indian translational platforms and, eventually, clinical evaluation. Sourcehttps://tinyurl.com/27f47ceshttps://tinyurl.com/y7gr57h7https://tinyurl.com/234yluryhttps://tinyurl.com/25j2eoymhttps://tinyurl.com/2439b93ghttps://tinyurl.com/2ycmkfc5https://tinyurl.com/23w6v6cthttps://tinyurl.com/23rquw3uhttps://tinyurl.com/23534t47

What Do Lizards in Czech Gardens and Indian Fields Teach Us About Conservation?

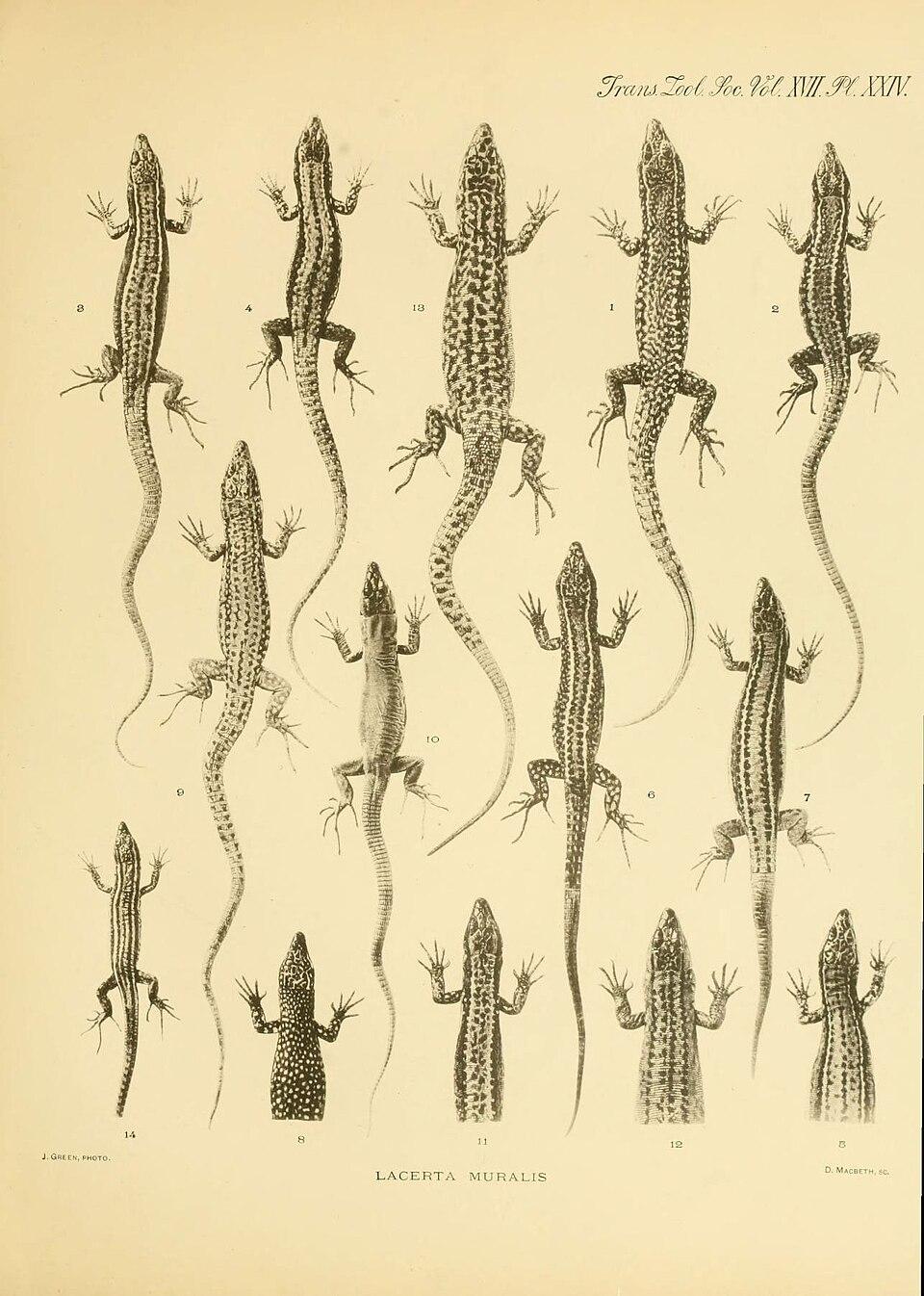

Because of their behavior and small size, lizards live close to people. They inhabit the cracks in garden walls, the sunlit stones of old ruins, the margins of paddy fields and the thorny hedges that separate one smallholding from another. They are ordinary enough to be overlooked, and curious enough, in form, behaviour and life cycle, to draw the attention of naturalists. Across two very different geographies, the Czech Republic and India, recent field reports and conservation notes remind us of two linked truths: that lizards do quiet but vital ecological work, and that their fortunes depend on the tiny features of the landscape which we can easily lose.A brief natural history note is useful. Lizards are a broadly diverse group of reptiles; some are tree-dwelling geckos, others rock-clinging lizards, and many feed mainly on insects. Their life cycles and activity patterns are tightly tied to local climate and habitat structure, and because of their small home ranges they often respond quickly to local environmental change. For gardeners and farmers this is good news: where lizards persist pest insects are kept in check; where they disappear, other signs of a simpler, less healthy ecosystem soon follow.Czechia’s stones, northern surprisesOn soils in the Czech Republic long-known species such as the European green lizard and various wall lizards occupy warm, open habitats — limestone outcrops, old masonry and sunlit embankments — and are familiar to anyone who spends time outdoors. Regional field guides and checklists name these species among the most visible representatives of the country’s reptile and amphibian life.Yet the record from the Czech Republic also contains surprises. Reports noted a Balkan wall lizard population well to the north of its previously understood range, a discovery that either records a recent northward expansion or uncovers a relict population that had been overlooked for decades. Finds at the edge of a species’ range matter: populations at the margin of a species’ distribution often carry distinct genetic variants and adaptations, and they change how we decide what and where we must protect. This is a reminder that even in a small country we should not assume we know where a species begins or ends; careful surveying can rewrite those boundaries.Zoos and husbandryConservation in the Czech Republic is not only a matter of field lists and range notes. Zoos have played a practical role in reptile and amphibian work, developing husbandry techniques and maintaining insurance populations. A zoo announced a notable captive success: the birth of a rare monitor lizard under controlled conditions, an event that advances the breeding knowledge so necessary for any potential reintroduction effort. Captive, off-site work like this serves two linked purposes: it safeguards genetic material when wild populations are precarious and it builds the craft of care that conservationists may need in an emergency.India’s scale and conservation practiceMove east, and the story broadens. India’s reptile fauna is very diverse. From riverine crocodilians to small skinks and agamid lizards, the country supports a great variety of groups, many of them found only in small areas. Alongside institutions, individuals have shaped modern conservation practice there. Their work — founding a crocodile conservation centre, training local communities and establishing cooperative, livelihood-linked models such as a cooperative of snake catchers — shows how conservation in India has often been practical, local and socially embedded. This approach is a clear lesson in combining fieldwork with community engagement, turning fear into stewardship.Yet India’s agricultural and developmental landscape places severe pressures on reptile life. A considered review argues that farmland reptiles and amphibians are especially vulnerable to agricultural intensification. Hedges, field margins, seasonal ponds and uncultivated patches, the small habitats that sustain reptiles and amphibians, are often the first features to be lost when farms are modernised. The review argues, with data and practical advice, that simple, low-cost measures, retaining hedges, conserving ponds, reducing pesticide use, can make farmland friendlier to reptiles and amphibians without threatening productivity. Put bluntly: conservation for reptiles in India begins in the margins of fields.Citizen networks and the data commonsAcross India the bringing together of sightings and photographs into national websites has become a powerful tool. National online resources that bring together species accounts and images turn casual observations into confirmed records and help prioritise places for protection. In a landscape where many species occur in tiny, isolated pockets, a single confirmed locality can change conservation decisions. Citizen science thus matters as both an early warning system and a mapping tool, a way for ordinary people to contribute directly to the record that conservationists use.Gardens, fields and small things that matterIt is worth pausing on the humble garden. Gardening guides emphasise the ecological services lizards provide in domestic and cultivated spaces: they consume pests, require little space, and signal the presence or absence of harmful chemicals. Encouraging lizards in home gardens is straightforward — retain rocks and leaf litter, reduce pesticide use, plant native species — and the benefit is immediate. Such local, low-cost measures reconnect the scale of everyday life with species-level conservation.A common lesson from two placesWhat links a northward wall lizard in the Czech Republic and India’s plea for farmland hedges is not a single method but a shared attention to small things. At a zoo the careful captive breeding and the new range records both expand our knowledge of what is possible; in India community-based conservation and an analysis of reptiles and amphibians on farmland point to what is necessary. Both contexts ask for patient observation, keeping small habitats, and an acceptance that conservation often succeeds at the scale of a garden wall, a seasonal pond, a patch of scrub — not only at the scale of reserves and announcements.If conservation is to persist it must be locally minded. Protect the stone ledge, spare the hedge, retain the pond; care for the small things and lizards will continue, in their common, remarkable way, to remind us of what the landscape once was and what it might yet become. Sources:https://tinyurl.com/6956v33 https://tinyurl.com/2yhkdtjk https://tinyurl.com/2a28ws25 https://tinyurl.com/2yalhzso https://tinyurl.com/2dkdlr4l https://tinyurl.com/2y8nsohz https://tinyurl.com/2dfxyreh https://tinyurl.com/22jgn4mh

Batanagar concerts and more, have connected India and Czech Republic in harmony over the decades

Small things often reveal a larger story: a programme note from a concert, a wartime theatre bill tucked in a private album, a short embassy press release announcing a choir’s tour. These are the scraps that stitch together the story of India and the Czech lands, connected through music! It's a shared history that moves between the concert halls of the factory town of Batanagar, the music schools of Prague, diplomatic gala nights in New Delhi, and the surprising moment when a Czech orchestra played old Bollywood songs for an Indian president. Read together, these modest artifacts show music as a living bridge between two curious societies.The first example takes us to Batanagar, the Bata township outside Calcutta in India. In October 1943, some sixty Czechoslovaks who had settled in Batanagar performed a Czech comic opera to a packed house at the New Empire theatre; the evening began with Dvořák’s New World Symphony. That small, jubilant event , recorded in oral histories and later gathered by music historians , is more than a local anecdote. It is evidence of how industrial migration (the Bata company’s transplant of Czech workers and managers to India) carried its culture with it: songs, operas, and ensemble pieces that became part of a shared civic life in colonial Calcutta. The Batanagar concerts remind us that cultural diplomacy is not always staged in the capital city's venues; sometimes it happens in factory town squares too.A second, more recent episode brings us back to Prague. when the Martinů Czech Philharmonic, conducted by Debashish Chaudhuri , a Calcutta born conductor trained partly in Prague , performed a concert hosted by the Calcutta School of Music. The program included Dvořák and local favourites; at one point the encore became a sing along to a popular Bengali song. The image is telling: a Czech orchestra conducted by an Indian maestro, performing Dvořák to an Indian audience and ending on a Bengali encore. That moment summed up long histories of support, migration, and learning in a single, audible event. It also shows a two,way musical exchange: Czech musicians in India learning Baul folk songs, Indian conductors leading Czech orchestras.Music and memory also appear in smaller institutional records. The Czech Embassy in New Delhi’s “Singing for Masaryk” programme in April 2017 brought a choir from Louny and staged a musical story imagining a symbolic meeting between Rabindranath Tagore and Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. The scene , a Czech choir singing in Delhi in English, Czech and Hindi, with the ambassador invoking shared ideals of independence , is typical of official cultural diplomacy: modest in scale, rich in symbolism, and carefully staged to underline continuity in relations. That same embassy has been active over years bringing Czech puppetry, recitals and folk song events to Indian audiences as well; boosting cultural diplomacy further.Another strand in this musical weave is the role of refugee musicians and cross, cultural composers. Walter Kaufmann, a Czech born musician who became director of European Music at All India Radio in the 1930s, is credited with composing the AIR signature tune, which some say was inspired by an Indian raga. These are the small biographies that matter: musicians displaced by political turmoil arriving in India, taking up posts in broadcasting and conservatory life, and in the process shaping local music with European techniques. The result is a clear blend , tunes, recurring motifs and orchestration that speak of refuge, adaptation and creative exchange.Indian Folk MusiciansPersonal and institutional threads meet again in a scene reported years later: a Czech orchestra performing a program of old Bollywood songs for India’s President. When an orchestra trained in Western symphonic tradition plays the tunes of another nation’s film songs for its head of state, the performance is not merely entertainment. It is a formal recognition of cultural ties and an act of cultural diplomacy , a reminder that musical memory crosses language and political borders. News reports noted the delight of listeners and the careful programming choices that made the concert both accessible and dignified.There are also quieter teaching links that sustain this relationship over decades. The Calcutta School of Music and similar institutions have maintained links with Prague music schools; Indian students trained in Europe have returned as conductors, teachers and cultural entrepreneurs. At the same time, Czech universities teach Bengali and other Indian languages; scholars in Prague lecture and publish on South Asian topics, and Czech choirs learn Hindi and Bengali songs for their tours. These exchanges , classroom by classroom, rehearsal by rehearsal , create a durable musical literacy that builds lasting ties. Institutional pages and contemporary portals describe how such collaborations are organized.If one steps back from these examples the broader pattern is clear. Music has been a medium through which industrial migration (Bata’s township), refugee resettlement (European musicians in India), cultural diplomacy (embassy choirs and festivals), and modern concert exchange (Czech philharmonics touring India) have all found a common language. Festivals, from the local Namaste India events in Prague to embassy nights in New Delhi, stitch together informal appreciation and understanding, and formal statecraft. Even when political currents shifted, from colonial rule to independence for India, from Cold War alignments to EU integration for the Czech Republic, the musical ties have proved adaptable, serving both as a comfort in exile and a resource for use in diplomacy.One last snapshot will close this short survey. Imagine an old concert poster folded into a family album: on one side, the Czech names of a choir and the date of an April evening recital in New Delhi; on the other, a newspaper clipping of the Martinů Czech Philharmonic performing in Calcutta under an Indian conductor. These small objects - programmes, clippings, embassy press releases , are the primary documents of cultural history. They tell us that friendship between nations is not only negotiated in ministries but also rehearsed in practice rooms, celebrated in town halls, and recorded in modest programme notes that future historians will one day find.Sources:https://tinyurl.com/262zg2mlhttps://tinyurl.com/22dh8dt5https://tinyurl.com/28abhpd3https://tinyurl.com/y7ulkxfehttps://tinyurl.com/2bv5kzekhttps://tinyurl.com/2c46bblmhttps://tinyurl.com/2b7r92gfhttps://tinyurl.com/292469dc

Shared Biodiversity: White-toothed Shrew Discovery in Czechia & Himalayan Snow Leopard Research in India

By the close of a recent field season in western Czechia a small, sharp-nosed visitor quietly rewrote a local checklist of mammals. Trapped by accident while researchers set live traps for house mice, the greater white-toothed shrew turned out to be a species not previously recorded in Czechia! 14 white-toothed shrews were captured during the survey amongst 446 small mammals. The shrew has been registered as the country’s 90th mammal. It was careful trapping and then DNA analysis that revealed the newcomer, a tiny carnivore whose pale, unpigmented teeth give the species its common name and whose appetite for invertebrates (and occasionally small vertebrates) sets it apart from the rodents it superficially resembles. This Czech discovery is seen not merely as a local curiosity but as one more marker of range shifts in a warming Europe: scientists note that the species’ spread north and west is plausibly linked to changing temperatures and altered habitats.The Czech record is infact modest and precise: a handful of trapped animals and a laboratory confirmation, yet it carries wider meanings. Naturalists and mammalogists watching shrew distributions elsewhere have documented ecological impacts when Crocidura russula expands into new areas: displacement of smaller native shrews and shifts in small-mammal community structure have already been reported in parts of western Europe. The Czech narrative therefore arrives as a small but vivid example of how local inventories and genetic methods together detect continental change.Half a continent (and many disciplines) away, India’s conservation science has been moving in a different way but toward the same aim: to measure, to understand, and to manage biodiversity. The Wildlife Institute of India (WII) — a national central body for wildlife research and training established in 1982 — carries a broad mandate that explicitly includes conservation genetics and wildlife forensic capabilities. Its website and projects list a dedicated Wildlife Forensic & Conservation Genetics unit and laboratories that support genetic monitoring, population assessment and species recovery programmes across India’s great eco-regions. These are the methods that allow managers to move beyond sighting reports to robust, replicable population estimates and genetic assessments of endangered species.WII’s recent public reports make this concrete. The Snow Leopard Population Assessment in India (SPAI), a national exercise coordinated by WII and partners, produced the first scientifically rigorous national estimate for the species; the programme’s outputs and related WII reports have been shared by the institute. Elsewhere on WII’s website one finds long-running studbook and monitoring efforts for both snow leopard and red panda, and a suite of projects that treat the Himalayan landscapes as living laboratories for genetics-informed conservation. In short, India’s premier wildlife institute is building and maintaining the technical backbone needed to map population trajectories, detect genetic bottlenecks, and guide interventions.If WII lends technical depth, the Zoological Survey of India supplies scale. ZSI’s annual compilation — Animal Discoveries 2023: New Species and New Records — assembled the country’s taxonomic outputs for the year and documented hundreds of additions: the 2023 volume records some 641 discoveries, including several hundred species that are entirely new to science and dozens more recorded in India for the first time. Taken together, ZSI’s yearly compilations are a catalogue of Indian biodiversity’s living richness and of the steady, patient work of taxonomists, field biologists and museums that continue to map life even as habitats change. The breadth of those lists is a reminder that while one small shrew can make headlines in Central Europe, in India the story is often told as a continual accumulation of newly understood diversity.Two narratives meet, finally, at the level of policy and partnership. In January 2024 India and the Czech Republic formalized a Strategic Partnership on Innovation that explicitly names the environment, environmental sciences and researcher mobility among shared priorities. The joint statement lays out an ambition to deepen high-level and academic exchanges, to promote cooperation in biotechnology and environmental research, and to facilitate the movement of scientists for joint projects. That is the framework by which a Czech field team and an Indian genetics laboratory can, over time and by design, collaborate. It makes joint calls for research, shared datasets, and people-to-people links for comparative ecology possible across continents.The diplomatic line is echoed in practice. The Czech Embassy in New Delhi has hosted insect research exchanges and the launch of a field guide to Karnataka hawkmoths co-authored by Czech and Indian researchers. Czech collections are among the world’s largest for Sphingidae and that a shared research programme had already yielded species not yet catalogued in global registers. Such projects are small, focused, and richly symbolic. Another case study of taxonomic collaboration on moths is as much about specimen cabinets and field notes as it is about building the trust and institutional channels needed for larger, cross-disciplinary work.Taken together, these threads describe a contemporary conservation geography in which local discovery, national capacity and bilateral policy loop into one another. A shrew trapped on a Czech farm is confirmed as a Mammal by DNA; a snow leopard count is possible because of camera networks, studbooks and genetic labs; a yearbook of new Indian species compiles the labours of taxonomists across states; and a strategic partnership provides tools for future joint projects. Each element matters: field traps and field guides, genomes and government statements, museum drawers and memoranda of understanding.Where does this leave the reader — and, perhaps more importantly, the policymaker or the young researcher? It leaves them with a modest but firm lesson: biodiversity is simultaneously local and global, easily displaced and well documented. The smallness of a shrew and the grandeur of a Himalayan cat occupy the same intellectual landscape when institutions share tools and data: genetic labs, monitoring protocols, and the diplomatic support to let scientists cross borders and compare notes. The challenge is to ensure that those crossings are not occasional headlines but sustained practice — in the form of continued field surveys, continued taxonomic work and sustained, funded collaboration that binds a yard trap in Czechia to the Indian camera trap in a shared effort to understand and conserve life on our ever changing planet.Sourceshttps://tinyurl.com/2cg9gqv9 https://tinyurl.com/25yoryaj https://tinyurl.com/244vus5h https://tinyurl.com/29hxl78p https://tinyurl.com/23tk28n2 https://tinyurl.com/25ugcvnz https://tinyurl.com/2yj6c3pl

The weave of history, trade and cultural memory in the traditional textiles of India and Czech Republic

A small object often tells the largest story: a folded fragment of handloom tucked into a museum drawer, its selvedge still bearing a dye mark, its wear-pattern a map of hands and seasons. In all, that scrap becomes a narrator. Such items, as a block-printed Indian kalamkari fragment, a Czech bobbin-lace panel or an embroidered border from an Indian sari — are the primary documents of textile history, and they show how cloth binds communities, trade routes and memory. Museums on both sides — from India’s rich textile galleries to the Museum of Textile in Česká Skalice and the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague — collect these small evidences, and together they map a shared human attention to texture, technique and meaning. India’s textile story is ancient and continuous. Archaeological and textual evidence place cotton spinning in the subcontinent millennia before the Common Era and silk weaving in later classical times. Beyond technique, cloth has always been worn with its own social significance. Courtly muslins, temple brocades, and regional specialities such as Benarasi brocade, Kanchipuram silk, Kantha embroidery, Ikat and block-printing traditions represent a dense cultural archive. These crafts were historically located in specific towns and were in the nature of specialized skills — the perfume of a dye vat in a certain lane or the cadence of a weaver’s shuttle echoed in another family across genealogies. These later became the craft centers compiled and explained in museum collections and trade histories. In Bohemia and Czech lands the textile story took different technological turns but was equally expressive. Lace-making, folk embroidery, and later industrial weaving and textile manufacture left a durable imprint on local culture and industry. Museums such as the Museum of Textile in Česká Skalice preserve bobbin lace, patterned linens and the machinery of industrial production that tell the story of centuries of local skill and modern mechanization. The Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague holds ornamental textiles and fashion objects that place Czech textile traditions in conversation with broader European currents of design and utility. Together these Czech collections — fastidiously catalogued garments, lace panels and factory implements — function as local memory-banks, preserving techniques and social uses that resonate with Indian forms of material patrimony. A précis in objects helps: consider a museum drawer in India in Ahmedabad or Calico’s galleries (which house courtly brocades, resist-prints and weavers’ samples) and a display case in Česká Skalice with worked linen and a nineteenth-century bobbin lace collar. One is the residue of handloom economies, linked to and in servitude to the city palace and the main temple by supplying them textiles and garments; the other, being the living trace of household dress and the region's sartorial practices. Both are fabric biographies. These comparative vignettes show that although techniques differ — warp-face vs. weft-faced weaving, shuttle vs. bobbin lace — the cultural function of textiles is analogous: to index identity, ritual and status. Textiles also map trade and industrial change. India’s handloom sector has long been a major source of livelihood and export; scholarly surveys trace a trajectory from artisanal production to episodes of mechanized challenge and then to renewed interest in handloom’s cultural value. Contemporary research paints a complex picture: while industrial mills and global competition have stressed handloom weavers, domestic and international demand for authentic, artisanal cloth remains a strong countervailing force. Trade papers and research syntheses emphasize the role of regional hubs (textile fairs, clusters around cotton production centres and silk towns) in maintaining skills and channeling exports.That economic axis reaches into Europe. Export tables and market notes show that cottons, silks and crafted textiles have long been part of India’s trade portfolio; modern trade coverage situates textiles within shifting export strategies and new markets. While the Times of India piece on export realignment focuses on changing geographies of Indian textile export (and the search for alternate markets), the material fact remains: cloth moves — by ship, rail and now air — and with it flows knowledge of finishing techniques, dyeing and quality control. Czech importers and European designers form one of the several ends of that chain, buying raw weaves, specialty fabrics and artisanal cloth pieces for both commercial and museum use. Preservation is a shared institutional activity. In India the National Handicrafts and Handlooms Museum and city museums conserve looms, patterns and practitioners’ memories; in the Czech lands, decorative art museums and textile museums preserve lace plates, weaving cards and mechanized looms that once powered local economies. These institutions are not mere warehouses; they are active sites of pedagogy and revival — exhibiting, cataloguing, running workshops, and sometimes hosting residencies where contemporary designers learn old techniques. The Sanskriti Museums and other cultural trusts in India as well, act as incubators for reviving techniques, mounting exhibitions that bring artisans and urban publics into direct encounter. Tamil, Painted Textile Wall hanging, c. 1640-50; possibly made for King Tirumal Nayak of MaduraiThe craft is not without modern trials. India’s handloom sector, while culturally central, faces structural problems: fragmented production, low returns for weavers, competition from mechanized mills and imports, and intermittent policy support. Scholarly literature documents both historical resilience and contemporary vulnerability: the handloom sector’s survival depends on market access, design innovation, social protection for artisans and better supply-chain linkages. In short, the textile heritage must be combined with economic pragmatism: branding, traceability and better returns for weavers if traditions are to be kept alive. Sustainability is the contemporary thread that joins old practice to new imperatives. Natural fibers and low-energy processes in traditional handlooms offer ecological advantages over synthetic, energy-intensive production. Yet even here tradeoffs exist: the sustainability of sandalwood-stained silks or indigo vats depends on sourcing practices, scale and certification. Both Indian and Czech stakeholders — museums, designers and exporters — increasingly talk about certification, fair trade labeling and traceable provenance as ways to preserve ecological and cultural value while accessing European markets that prize ethical sourcing. Such practices offer a route by which textiles can be both a preserved heritage and a marketable commodity. Finally, a small archival vignette will closes the pattern: imagine an old invoice folded into a weaver’s notebook. On it: “20 pieces madras checks — shipment to Prague — 12th March 1936.” Folded beside it, a museum accession slip from Česká Skalice records receipt of a lace collar from a Czech farmhouse, dated 1898. These two small pieces of paper — an export invoice and a museum accession note — are the quotidian evidence of the centuries-long exchange. They show how textiles travel not only as commodities but as culture, how cloth carries memory, and how museums and markets together keep that memory in conversation. Sources:https://tinyurl.com/nrrx962https://tinyurl.com/23xlv3n6 https://tinyurl.com/nrrx962 https://tinyurl.com/2c9x7a3e https://tinyurl.com/235n8bbq https://tinyurl.com/2yu3wryp https://tinyurl.com/253aaapo https://tinyurl.com/2d7f8ftx https://tinyurl.com/26hjxkj6

How have Indian and Czech artists exchanged ideas through modern art ?

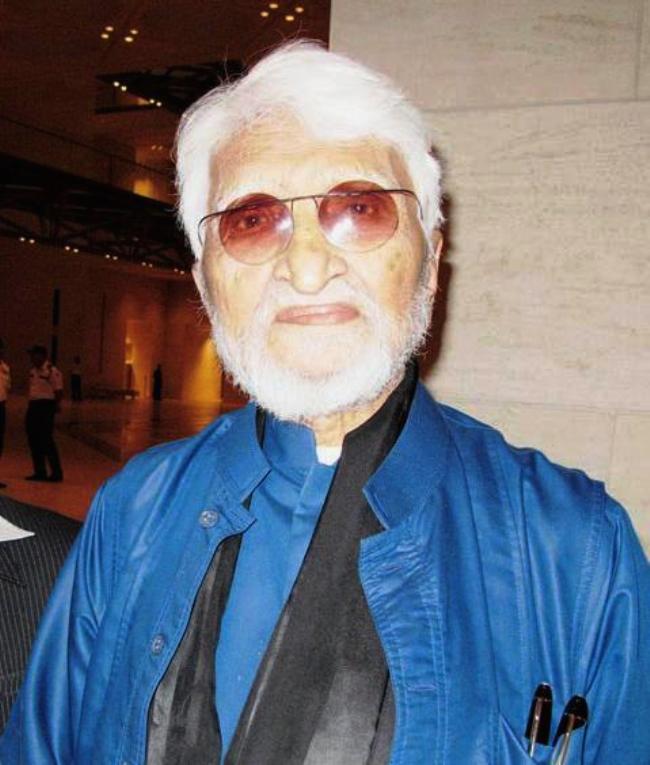

By the first decades of the twentieth century, artistic itineraries had become another way in which distant worlds narrated one another. Painters from the Czech Republic traveled to Ceylon and India with the same mixture of idealism and inexperience that marked many an expatriate venture (they often set out without money or knowledge of English language), and the works they brought back—oils, linocuts, illustrated memoirs—created durable threads between Prague and Calcutta, Bombay and Santiniketan. These threads, visible in exhibition catalogs, museum accession lists, and the occasional auction note, reveal a clear reciprocity: Indian modernism entered institutional collections in the Czech Republic even as painters from the Czech Republic absorbed Indian landscapes, people, and print traditions into their own visual vocabularies. This reciprocity appears in three overlapping registers: through the painter-travelers Jaroslav Hněvkovský and Otakar Nejedlý (their journeys, hardships, and exhibitions), on the one hand, and the international circulation of politically charged prints by India artist Chittaprosad Bhattacharya (and his Prague friendships) on the other hand, and the way institutions in the Czech Republic, above all National Gallery Prague, gathered works by major Indian modernists into a visible, if modest, canon.The case of Jaroslav Hněvkovský is emblematic. Known in the Czech Republic as the “Painter of India” and sometimes celebrated as a “Slavic Gauguin,” Hněvkovský’s India years are described as the period when his subject matter and reputation crystallized. An Untitled, 1911 produced, 66 x 76.2 cm oil painting, depicting a Jungle Scene in Kerala, place Hněvkovský within two complementary stories: a romantic artist-traveller who spent several seasons painting in the subcontinent, and secondly as an exhibitor whose Indian work made a European circuit. There is a small, important discrepancy in the accounts over the precise year of the first voyage—some date the journey to 1909, others to 1911—but consensus is that a protracted Indian stay produced a body of jungle and city views that later circulated in London and Prague. Accounts also refer to his meeting with Rabindranath Tagore, who invited him to Santiniketan. The artist Otakar Nejedlý’s trajectory runs alongside Hněvkovský’s..Nejedlý—born in 1883 and later a professor at Prague’s Academy—accompanied Hněvkovský to Ceylon and India; his memoirs and biographical entries narrate the voyage’s hardships (poverty, illness, malaria) and the pragmatic reasons that compelled an early return to Europe (Nejedlý returned in 1911 while Hněvkovský stayed on). Nejedlý’s published recollections, a book of impressions from Ceylon and India appeared in 1916, and his later role as an influential teacher indicate how experience abroad fed back into artistic life in the Czech Republic: travel produced both pictures and pedagogy. Visual traces of these survive in reproductions and image captions that consolidate the painter’s reputation across museums and online archives.A second strand of exchange was more political: manifested in the circulation of prints and in the solidarity it generated between the 2 countries. Chittaprosad Bhattacharya—the Bengali artist whose representation of the famine of 1943–44 and the subsequent production of linocuts testified to an engaged, left-leaning graphic practice— and it thereby sustained a long association with Prague and its people. Czechoslovak networks (institutions, journals, and individuals) took up his work: linocuts by Chittaprosad entered National Gallery of Prague in the early 1960s; his works and illustrations circulated in the journal Nový Orient/New Orient Bimonthly; and personal friendships, notably with František Salaba (assistant to the Czechoslovak trade commissioner in Bombay, 1954–57), led to practical support. Salaba not only organized exhibitions of toys and puppets in Bombay but also gave Chittaprosad puppets and a stage—material aid that enabled the artist’s Khelaghar puppet theater for children in Andheri, Mumbai. These are the kinds of biographical details that show cultural exchange as durable, embedded, and occasionally asymmetrical: Prague supplied platforms, journals, and friends; Chittaprosad contributed images, scripts, and political urgency that resonated with socialist cultural networks.The Prague side of the exchange was institutional as well as personal. National Gallery Prague’s Department of Oriental Art (established by decree in 1951) now manages a collection numbering in the tens of thousands, and within its South and Southeast Asian holdings the museum lists 20th-century Indian prints and paintings, including names familiar to any history of modern Indian art: M. F. Husain, Ram Kumar, Biren De, and Chittaprosad. This institutional fact—that these artists appear on the Gallery’s lists—matters for how national canons are imagined; it suggests that the Czech Republic’s gallery acquisition policy, from the mid-20th century onward, actively incorporated modern South Asian art into its narrative of global modernisms. The Gallery’s Asian collection thus serves as an archival hub connecting Prague to multiple modernisms: the woodcut and linocut circulations, the pedagogical legacies originating in Bombay’s art schools, and the transnational solidarities that animated postcolonial cultural exchange.M. F. HussainFinally, a brief word on context: European academic realism and the institutional infrastructures that brought oil painting and studio pedagogy to Indian art schools also shaped what foreign visitors encountered. Overviews of the academic tradition emphasize the role of schools such as the Sir J. J. School of Art and the wider diffusion of European techniques in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; these pedagogical currents formed the background against which both Indian modernists and visiting Europeans worked, taught, and displayed their works. That context helps to explain why a Santiniketan invitation—Tagore’s appeal to Hněvkovský to teach—would have seemed sensible to both parties: one side sought new forms and expressive vocabularies; the other had technical mastery to share.Taken together, these documentary strands suggest a pattern that is modest but unmistakable: painters who left Prague for the subcontinent returned with canvases, memoirs, and professional reputations; Indian printmakers and political artists found in Prague's journals, curators, and friends a receptive and helpful audience; and cultural institutions in the Czech Republic, over decades, collected works by Indian modernists and socially committed artists, thus stabilizing a cross-regional archive of modern art. The exchanges were not symmetrical, and they were not merely aesthetic: they were also pedagogical, and at times ideological. Yet from the jungle scenes of Kerala to the linocuts of a famine-era Bengal, from a puppet stage in Andheri to a gallery accession list in Prague, visual art forged concrete bonds across an ocean and across cultural differences—bonds that survive in canvas, catalogue, and correspondence.Main Image: Inside Sternbersky Palace, PrahaSources:https://tinyurl.com/2c5uqxomhttps://tinyurl.com/249gg6x4https://tinyurl.com/29goyfouhttps://tinyurl.com/222oy8nrhttps://tinyurl.com/y7h852cdhttps://tinyurl.com/2yhcqqzjhttps://tinyurl.com/2cqnfmvmhttps://tinyurl.com/28hvd5dw

Krkonoše vs Kaziranga: Return of the Apollo Butterfly in Czechia & Citizen Science in India

By instinct and by necessity, butterflies live on the edge. Their lives are governed by host plants, by the timing of flowering, by mowing schedules and grazing, by the light that falls on a limestone slope or a forest glade. Because their needs are small and very specific, they are also among the best indicators we possess for the health of a landscape. Where butterflies thin out, the soil, the hydrology and the mowing regime have already been altered; where they flourish, the small-scale structure of habitat has been kept intact. Two recent strands of work — the careful, institutional return of the Apollo in mountains in the Czech Republic and the rapid growth of community-driven butterfly recording in India — show how different societies are reading those signals and acting on them.One clear statistic is a good place to start. Reports from Central Europe note the serious scale of insect loss in the region: insect numbers have fallen by as much as 75 percent over the past thirty years. That collapse is not just a vague warning; it is the context against which projects to restore butterflies must operate. If insects in general are in retreat, bringing back a demanding species like the Apollo requires more than a release event: it requires rebuilding a meadow from the ground up — with stonecrop present, grazing schedules adjusted, shrubs cleared and mowing timed to allow caterpillars to complete their cycle.The Apollo is the emblem of that practical patience. Parnassius apollo — large, pale, marked with red eye-spots — once flew on slopes in the Czech Republic but was locally lost about a century ago. Reintroducing it has been a project of habitat reconstruction as much as of captive breeding. In June 2024, the JARO Group released fifty captive-reared Apollos into a prepared site in the Krkonoše (Giant) Mountains; the release followed years of habitat work and careful breeding, and it was planned as a test — the released males were meant to stay and show whether the restored conditions were sufficient. The project is part of a wider European-supported network that links partners across Central Europe, and its message is practical and simple: restore the meadow, restore the host plant, and only then consider release. Monitoring must follow.Closely related is the quieter, incremental work to save the clouded Apollo (Parnassius mnemosyne), a specialized species of lowland woodland edges. Czech entomologists have documented severe local declines and responded with targeted interventions: increasing sunlight in selected forest patches, preserving the Corydalis food plants of caterpillars, and creating corridors between remnant sites. In one restored preserve the clouded Apollo’s numbers rose from a handful back to several hundred after management changes — an instance where a specific change in forestry practice (less logging, less broad herbicide use, controlled grazing) yielded clear biological results. The lesson is clear: butterflies respond to small habitat changes.If Central Europe’s work has been corrective — to bring back what was lost — India’s work is largely protective and proactive. India still has extraordinary butterfly diversity, but that wealth sits beside powerful threats. Recent reports and field reviews warn that South Asian butterflies face rising risks from habitat loss, urbanisation, climate change and pesticide use; reports describe how mangrove and forest systems and urban greenspaces are all vulnerable, and they warn that large-scale policies and funding still prioritise large, popular animals over insect conservation. The consequence is obvious: remarkable diversity persists, but only so long as local habitats and the people who steward them remain vigilant.Some conservation numbers are striking. Kaziranga National Park — known internationally for its rhino and elephant populations — was recently recorded to support 446 butterfly species, making it one of India’s most species-rich protected areas. This record serves two purposes: it underlines the sometimes-hidden diversity of even well-visited parks, and it demonstrates how careful survey work can change management priorities for protected areas that have long been seen only for their large mammals. Recognising butterflies in such parks invites managers to think about floral corridors, nectar sources and seasonal wetlands alongside the demands of large animals.If institutional action matters, so does public engagement. India’s “The Big Butterfly Month”, the “Biodiversity Marathons” and an online platform for butterfly records have become a working network for butterfly knowledge. These initiatives turn casual sightings and photographs by school groups, photographers and walkers into usable records of where species occur. The Big Butterfly Month — first launched in September 2020 — and recurring Biodiversity Marathons link volunteers to a national Biodiversity Atlas; they supply coverage over time and place that formal surveys alone cannot provide. In a region where many species exist in narrow ranges, a single verified locality can change conservation decisions. Citizen science is therefore not just public participation; it is a primary source of data for policy and protection.Practical conservation work — whether in Krkonoše or in Kaziranga — shares common prescriptions. For the Apollo the immediate tasks were botanical and managerial: secure stonecrop patches, time the mowing and grazing so caterpillars survive, keep shrubs at bay and restore open, sunlit meadows. For Indian sites the tasks are many but often simple: spare a field margin, protect a seasonal pond, reduce pesticide sprays along hedgerows, record sightings and publicise local occurrences so that managers see value beyond immediate economic returns. The day-to-day labour of conservation is ordinary: the correct mowing schedule, the retention of a few flowering roadside plants, the habit of photographing and uploading a single butterfly. Those low-cost acts add up.Two different places show the same approach. In Czechia institutional science — breeding protocols, European projects, and coordinated habitat restoration — has been essential to reverse local extinctions. In India a distributed network of enthusiasts, data marathons and targeted surveys is filling a long-standing documentation gap and turning observation into protection. Both systems must operate together: reintroductions without habitat will fail; records without action remain nice but unused records. Each butterfly that returns, each new locality documented, is a small but telling sign that the landscape can still be read and repaired.Sourceshttps://tinyurl.com/25ltkcgg https://tinyurl.com/2ywq3y7h https://tinyurl.com/27qxabwy https://tinyurl.com/2cwu8h5f https://tinyurl.com/225clwc3 https://tinyurl.com/2b33nt4e https://tinyurl.com/289v3vv6 https://tinyurl.com/2y8uywmp https://tinyurl.com/29jn9avz

Petals on the Plate: Czech and Indian Traditions of Edible Flowers

By the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries a curious movement has been at work in kitchens and markets alike: flowers, once destined chiefly for vases and festivals, have quietly found their way into the pantry. Across Europe, and in particular in Czechia, where recent work has mapped both culinary practice and phytochemical potential, blossoms are appearing on plates and in confectionery, offered as delicate garnishes or candied centrepieces. At the same time, in India a far older connection exists between flower and food: a web of household recipes, use in rituals and medicinal knowledge that treats petals not as mere adornment but as food and medicine, as ingredient and antidote. Read together, the Czech and Indian stories show overlapping themes: a respect for nature’s small harvests, a search for flavour and colour that is also a search for health, and a growing market that wants these fragile items recognised.In Czechia the literature has been, until recently, a patchwork of lab tests, gastronomic experiments and emerging trade. Recent work highlights the species most often studied (Rosa, Dianthus and Calendula among them) and lists phytochemical measures: total phenols, flavonoids and relative antioxidant activity. These are not trivial details. For chefs and food scientists the data provides useful comparisons: which blooms score high on antioxidant tests, which retain colour and texture after candying, and which can be brought to market with evidence of nutritional value. Yet a caution remains: lab measures do not by themselves prove clinical benefit. They show biochemical potential, a first step, not a conclusion, and practical obstacles remain: such as seasonality, shelf life and consistent handling.Commercial practice already illustrates those obstacles. Retail offerings commonly combine flowers with confectionery or fruit arrangements; the ingredient lists reveal that many commercial products sit within complex products and contain additives and dyes, and that allergen labelling is essential for risk management. In other words, a “flower on the cake” is often not a simple botanical; it is a commercial food product, subject to the same rules as any fresh produce: traceability, refrigeration, and a need for clear labelling. The market shows growing interest: segmentation by species, form (fresh, dried), and distribution channel suggests a growth trend in the coming years. These signals do not, however, replace independent trade data; they do indicate momentum and buyer interest, the reason small Czech growers and pastry chefs now speak of edible flowers less as novelty and more as a sustainable niche.India’s relationship with edible flowers is older, deeper and more embedded in daily practice. Regional accounts list familiar household flowers that move between the kitchen and ayurveda centres (mahua, banana flower, hibiscus, safflower and pumpkin blossom) and describe concrete uses: stir-fries and fritters, fermented beverages, teas and preparations that are as much therapeutic as they are culinary. Hibiscus, for instance, is used in infusions and in traditional remedies; mahua has a place in ritual and in rural diets; banana blossom is a common vegetable in many households. This picture brings together both culinary uses and phytochemical studies of Indian species and notes that traditional systems (Ayurveda above all) have long valued certain flowers for digestive, cooling or tonic properties.Scientific inquiry supports much of the promise, but with caveats. Across studies and lab tests a recurrent finding is the presence of polyphenols and flavonoids — compounds that register on antioxidant tests and that, in controlled tests, can scavenge free radicals or inhibit simple oxidative markers. But the body of evidence is uneven: many botanical studies are small-scale, tests use different methods, and human clinical trials are scarce. Media summaries tend to translate these results into encouraging headlines; however, it is wise to be cautious. The composition of a petal under laboratory conditions is only the first step; how it behaves in a tea or a brew or in food, what doses are realistic in everyday cooking, and whether measurable health outcomes follow sustained consumption remain open questions.Safety, therefore, must be central to any culinary revival. General guidance stresses two persistent cautions: not every garden blossom is edible, and source matters. Ornamental cultivars may be bred for colour or scent and can carry unexpected alkaloids or pesticide residues; wild foraging without botanical expertise risks mistaking a toxic plant. Commercial vendors try to manage this through labelling and by adding flowers to confectionery products, but that very adding raises questions about additives and about lower nutrient content. Post-harvest handling (washing, blanching, refrigeration) reduces microbial risk, and traditional preparations (fermentation, syrups, heating) historically served to neutralise bitterness or mild toxins; these kitchen practices overlap with modern food safety practice.Finally, a brief note on cultural convergence. The Czech interest in novelty gastronomy and the Indian continuity of floral cuisine converge on a single, telling point: both traditions treat flowers as a marker of place and practice. In Czech pastry and haute cuisine a rose petal or calendula or any other seasonal flower placed on a tart signals a certain artisanal care and touch. In an Indian household a banana blossom curry or a hibiscus tea signals family tradition, a respect for the health giving properties in nature's bounty, and of course seasonality. In either context the flower is a small record of taste, of local botany, of labour. If the market grows, and if chefs and smallholders sustain demand, the important work will be to secure the sources, to ensure safety and to fund the clinical research that can turn biochemical promise into sound dietary guidance.Thus the story of edible flowers is neither a fad nor a final answer: it is a living conversation between laboratory notes and kitchen practice, between market signals and grandmother’s recipes. The Czech and Indian tales together suggest that petals on the plate can be both pleasurable and at the same time an economic possibility, provided we attend to method, source and the real limits of current scientific evidence.Sources https://tinyurl.com/29xyxtsk https://tinyurl.com/2bbg7x37 https://tinyurl.com/24yzjspo https://tinyurl.com/27tt8z4o https://tinyurl.com/2cde6b7o https://tinyurl.com/2p38qt4n https://tinyurl.com/294k7c9q https://tinyurl.com/2cutmgqg

Peruc-Korycany Formation to the Balasinor Sands: How habitats diversified the European & Indian dinosaurs

In a limestone quarry north of Kutná Hora a chance outing in 2003 by Michal Moučka and his sons yielded a find that challenged a long-held local assumption — that, during the age of dinosaurs, what is now the Czech Republic lay entirely beneath the sea. The 40-centimetre femur they recovered was quickly identified by palaeontologists as the bone of a small iguanodontid herbivore, an animal that most likely browsed on shoreline conifers and was later rafted and buried in marine sediments. The discovery, the first uncontested dinosaur skeletal record from Czech Republic territory, carries a simple but powerful lesson: Europe’s Late Cretaceous landscape included island archipelagos where small, sometimes dwarfed herbivores lived out island lives.A published description of that material places the find in the upper Cenomanian Peruc-Korycany Formation — a near-shore deposit that preserves a mix of halophytic conifers such as Frenelopsis and laurophyllous angiosperms. The Iguanodontid strongly suggests small herbivores browsing at the margins of little islands, not roaming vast continental plains. The bone itself tells other stories: gnaw marks from sharks show it was scavenged during a sea-borne journey, while the rock record indicates a low-energy, near-shore depositional setting. In short, the Czech fossil is less about size and more about place, a reminder that Europe’s Mesozoic environments were complex mosaics of islands, shores and shallow seas that selected for particular life histories.On the other side of the world, the scene changes from islands to hatcheries. In Gujarat’s Raiyoli-Balasinor region palaeontologists have long recognised a landscape that, in the Late Cretaceous, favoured mass nesting and sauropod reproduction. Excavations beginning in the early 1980s revealed thousands of eggs and dozens of clutch sites; more recent fieldwork has expanded that catalogue further, documenting varied clutch morphologies and a high diversity of species assignable to titanosaurs. A large, museum-backed fossil park and a museum at Raiyoli now showcase the density of these finds — life-size reconstructions, galleries of eggs and bones, and public exhibits that make clear the site’s significance as one of the world’s great dinosaur hatcheries.Scientific work in the Narmada and lower Narmada valleys adds quantitative depth. A team working on Lameta Formation zoological material documented scores of titanosaur egg clutches and hundreds of eggs, describing circular, linear and combination clutch patterns, burial processes that preserved the nests, and microscopic details that point to nesting behaviour and reproductive biology — for example, signs consistent with sequential laying and colonial nesting. These data do not merely enumerate eggs; they let palaeontologists reconstruct breeding behaviour, depositional conditions and the palaeoecology that made such hatcheries possible: broad, sandy plains with shallow water bodies and low-energy depositional pockets where eggs could be buried, incubated and, in many cases, hatched.The Balasinor finds also yielded skeletal remains of theropods — notably the carnivorous Rajasaurus — and a broader faunal assemblage that speaks of a Cretaceous plains environment punctuated by rivers and interdune basins, a very different setting from the island archipelago preserved in Cenomanian Europe. Where the Czech Republic iguanodontid seems adapted to a shoreline, possibly constrained in size by insular conditions, Balasinor’s titanosaurs and the Rajasaurus ecosystem portray a landscape where large sauropods nested en masse and predators prowled river margins. The comparison is instructive: habitat sculpts opportunity, and opportunity shapes morphology and life history.Palaeontology in Rajasthan adds yet another habitat to the comparative map. Recent reports from Jaisalmer and the Lathi Formation describe a well-preserved phytosaur — a crocodile-like archosaur that points to freshwater and marginal marine environments in what is now the Thar Desert. The phytosaur fossil, found near a lakebed in Megha village, dates back to the Jurassic and suggests extensive aquatic life where semi-arid to coastal conditions later prevailed; it reminds us that the Indian subcontinent, across time and space, hosted an array of environments from coastal hatcheries to inland rivers that in turn shaped reptilian life, feeding strategies and preservation pathways.Beyond individual bones and nests, the record speaks of preservation and burial history. The Czech femur is found in marine sediments — the result of transportation and scavenging — while many Indian dinosaur eggs are preserved in sandy limestone and calcareous sandstones that record low-energy marsh and river settings conducive to nest preservation. Where European finds often survive as isolated bones washed out to sea, Indian sites such as Balasinor and the lower Narmada valley preserve entire nesting landscapes and clutch assemblages — a difference of both scale and depositional fortune. For the palaeontologist, these contrasts are not merely evocative; they are empirical cues about population density, reproductive strategy and mortality regimes.The comparative view has practical consequences for how we study the deep past. Small-island dynamics — dwarfing, constrained niches and high endemism — explain why some European dinosaurs remained medium sized; expansive floodplain nesting grounds in India explain prolific egg production and the high zoospecies diversity recorded in the Lameta. Meanwhile, isolated finds in Rajasthan expose aquatic corridors and shifting shorelines that once linked seas and rivers. Together they show how different habitats — islands, plains, river margins, coastal lagoons — created distinct evolutionary settings, each scripting its own responses in body plan, behaviour and reproductive biology.Finally, palaeontological practice itself is part of the story. The Czech find began as a hobbyist’s quarry walk and required university expertise to verify; in India, long-term Geological Survey programmes and more recent systematic surveys have transformed scattered curios into mapped hatcheries and museum collections, enabling integrated studies of palaeobiology and taphonomy. Both approaches matter — the serendipity of the field hand and the patient accumulation of regional data — for they offer complementary windows on ancient life.Sources: https://tinyurl.com/28wv4jwphttps://tinyurl.com/28sbyvmzhttps://tinyurl.com/2xqw2b2ehttps://tinyurl.com/28xmj2r9https://tinyurl.com/2a9bqlzohttps://tinyurl.com/2xrmv4r8https://tinyurl.com/25h7urwyhttps://tinyurl.com/25h7urwyhttps://tinyurl.com/2clb8hzo

The spiritual tradition of Yoga has united the hearts and minds of Indians and Czechs

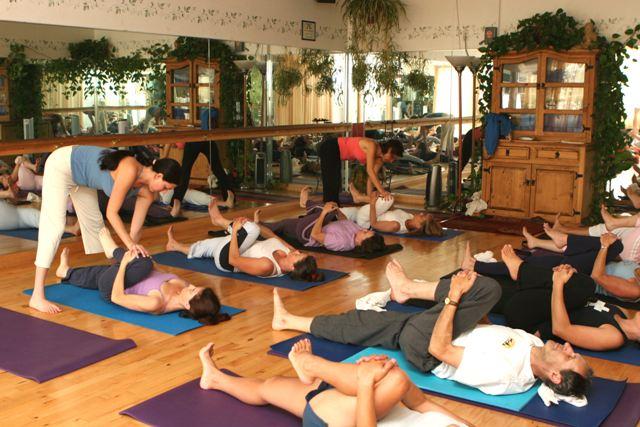

By its nature, yoga resists any single story. It is at once practice, philosophy and an array of institutional lineages — a living archive of texts, teachers and places that stretches from the riverbanks of ancient India to modern studio rooms in Prague. To follow that archive is to notice two parallel movements: Inward, as the long spiritual path toward “Samadhi” (as a discipline of breath, mind and ethical living); and outward, as twentieth- and twenty-first-century expansion of teachers, schools and civic initiatives that have carried those practices into global civic life. In this article we will see how these two movements meet: in institutions (the Bihar School of Yoga; Yoga in Daily Life), in global networks (the European Union of Yoga), and in local practice (retreats in Slavonice; Sahaja Yoga centres across Czech regions). Any careful telling must begin in India, where yoga’s spiritual grammar took shape. Travel accounts and contemporary guides remind us that what many Western studios present as “yoga” — an asana class, sometimes stripped of ritual — is only one limb of a much older system whose aims were ethical and spiritual as much as physical. Even now in India, the emphasis remains on spiritual discipline, on meditation and on scriptural study (the Yoga Sūtras, the Bhagavad Gītā) rather than merely on exercise. The asana, in this telling, is a preparatory technology to steady the body for inner upliftment. This is not a modern claim alone: commentators and modern teachers alike observe that the practice’s vocabulary (prāṇāyāma, dhyāna, the yamas and niyamas) is contiguous with Hindu philosophical categories, even as modern practice is plural and variegated. Yet that proximity to Hindu thought does not reduce yoga to a single institutional religion. Contemporary expositions by teachers emphasise nuance: yoga predates many world religions, it carries moral precepts and devotional practices in some lineages, and it can be taught as a largely secular technique in others. In short, yoga appears both as a spiritual technology embedded in Indian religio-philosophical traditions, and as a set of practices that can be adapted — sometimes deliberately secularised — for cross-cultural teaching (a point that underwrites much of the European reception). This paradox — sacred origin, plural contemporary forms — is one that institutions on both sides of the movement have learned to manage. Institutional anchors make that management visible. The Bihar School of Yoga (Munger, Bihar) is repeatedly listed in Indian institutional rosters and histories as a mid-twentieth-century attempt to systematise a holistic approach — a centre where asana, breath-work, meditation and daily discipline are taught as a joint program (the school is routinely cited in institutional directories as a prominent founding node of modern institutional yoga). Likewise, the organisation Yoga in Daily Life sets out an explicit spiritual lineage and global network: its pages describe an ashram-based heritage, a founder (Paramhans Swami Maheshwarananda) and an international fellowship whose aims include cultural appreciation and religious respect. These are not mere labels: they are functioning organisations that host retreats, charitable activities and centres “around the globe,” and they therefore exemplify the way Indian institutions have shaped the contemporary cultural life of yoga beyond India’s borders. Europe’s reception of yoga has its own story, one both scholarly and organisational. Academic overviews (a recent Brill chapter on “Yoga in Europe”) have traced how yoga moved from exotic practice to European public culture, while federations such as the European Union of Yoga (founded in 1971) irrigate the continent with a network of teachers, national federations and an annual multilingual congress at Zinal where invited Indian teachers regularly appear. The EUY’s institutional practice — a formal teacher-training syllabus, multilateral membership across national federations and a long history of annual congresses — illustrates the organizational weight behind yoga’s spread in Europe and the way European circuits have sometimes adopted a secularised, training-focused form of yoga while still inviting Indian teachers to speak and teach. (The Zinal congress, in particular, is repeatedly cited as a meeting place for cross-cultural exchange.) How do these macro-movements show up at street level in the Czech Republic? The evidence assembled here is concrete rather than rhetorical. YogaOmline’s Czech page records Indian teachers and retreats held in small Czech towns (Slavonice is named as a recurring retreat venue and an Indian teacher, Ashwani Bhanot, is mentioned as a visiting instructor), indicating the active flow of teachers and programs between India and Czech localities. Directory listings aimed at expatriates in Prague name specific centres (for example, Yogaspace near Anděl) and mindfulness teachers advertising bilingual classes; Sahaja Yoga’s centre listings show an organised presence across several Czech regions; and a mix of local and international organisations advertise workshops, retreats and teacher trainings. These local traces — a retreat notice, a Prague studio listing, a network map of meditation centres — highlight how yoga’s spiritual and physical practices have been woven into Czech civic life, sometimes as secular fitness, sometimes as devotional practice, and often as a hybrid that foregrounds wellness and cultural exchange. What unites these varied threads — ancient scripture and modern studio, ashram and Zinal congress, Bihar School and a Slavonice retreat — is a shared grammar of encountering difference with respect. Indian institutions offer lineage and a pedagogical frame; European federations provide curricula, certification and meeting places; local Czech groups translate both into practice rooms and community centres. The result is not a flattening of meaning but a plural archive: yoga remains, for many, an explicitly spiritual discipline bound to Hindu philosophical vocabularies; for others it is a tool for mental and physical health; and for many more it is both, learned with an eye to historical depth and local adaptation. If there is a modest moral to be drawn from this book-like geography, it is that cultural exchange — even in the realm of embodied practice — leaves traceable institutional footprints. A named school in Bihar appears in institutional directories; European union holds a multilingual congress; a Czech town hosts an Indian teacher’s retreat; and an international ashram lists centres “around the globe.” These are not abstract connections but archived practices: programmes, registrations, retreat notices and bulletin-board listings that together show yoga as both a sacred Indian heritage and a universal practice that can foster wellness, respect and meaningful cultural exchange. Sources:https://tinyurl.com/2djymvejhttps://tinyurl.com/2am4a333https://tinyurl.com/2yftvnf5https://tinyurl.com/2cgb2eq6https://tinyurl.com/23torlwfhttps://tinyurl.com/2436ye3ohttps://tinyurl.com/292hlb7khttps://tinyurl.com/2258ca4ehttps://tinyurl.com/2xqzz3pthttps://tinyurl.com/2ad53dcvhttps://tinyurl.com/29tfy3kahttps://tinyurl.com/24cyg3jxhttps://tinyurl.com/2cgrlhqx

How the Bohemian Sand Pink and India’s Biodiversity Hotspots are chapters of the same Conservation story