Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

By the close of the nineteenth century trees were doing much more than shading streets or furnishing lumber: they were repositories of identity. Nowhere is that truer than in two distinct national imaginaries — the Czech Republic’s linden (lípa) and India’s banyan (Ficus benghalensis). Each stands as an arboreal emblem, a living shorthand for cultural continuity and civic memory; each today also figures in the technical and political apparatus of conservation. Read together, they tell a simple story: national symbols live, they age, and they must be watched over with tools both old and new.

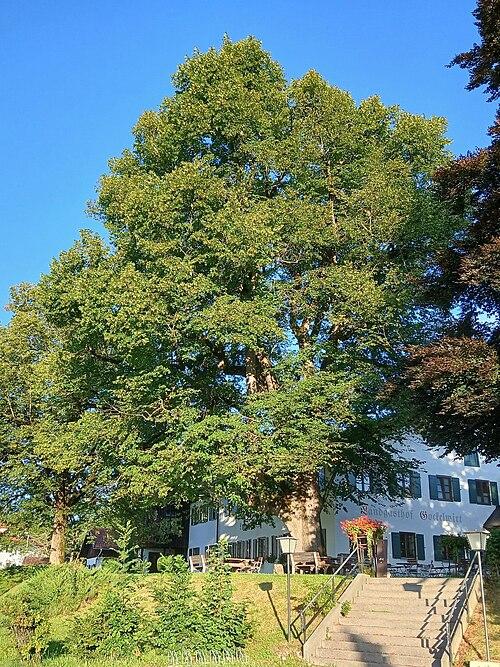

The linden in Czech life is both commonplace and consecrated. Rooted in Slavic folk practice and later absorbed into civic nationalism, the lípa appears across Prague’s squares, in the iconography of artists, and in the lore of villages where village greens were not planted beneath its boughs. Guidebooks and cultural accounts recall the tree’s pagan and Slavic associations related to protection, community and sanctuary — while popular histories note its material uses: a soft wood for instruments and carving, and a tree whose flowers and leaves have long entered household remedies and teas (popular accounts emphasise these uses while advising caution for pharmacological claims).

That cultural centrality has a civic corollary. Press reporting in recent years pointed to an extraordinary density of commemorative lindens: municipal surveys and local outlets report roughly three thousand such plantings across the Czech Republic, Slovakia and adjacent border districts — highlighting a civic habit of marking anniversaries with trees. This turns the lípa into a living ledger of memory. At the same time, singular trees have claimed public affection. An ancient “singing linden,” in Teleci, Eastern Bohemia, celebrated as Tree of the Year in 2021, is variously estimated at several centuries old — press accounts place its age at c.700 years and its girth at roughly twelve metres — and anchors local narratives of continuity and place (Radio Prague). Such venerable specimens, whether isolated monuments or rows along municipal boulevards, underline how botanical and civic histories interweave.

Botany tempers myth. The linden belongs to the genus Tilia — some thirty or so species across temperate Eurasia — noted for asymmetrical, heart-shaped leaves and a distinctive bract that aids seed dispersal. It is a tree much prized by beekeepers and urban planners alike: lindens flower prolifically and are often described as bee-friendly shade trees. Popular accounts and commercial pages expand the catalogue — speaking of teas, medicinal uses and great longevity (sometimes quoted in centuries or even a millennium!) — but these claims mix horticultural observation and folklore, and should be treated as part of the cultural story rather than immutable scientific fact.

If the Czech lípa carries civic inscription across Europe’s many squares and municipal projects, India’s banyan is a different, yet comparable, kind of public emblem: grand, communal and mythic. Ficus benghalensis is widely cited as India’s national tree; its cultural valence is immense. In village life the banyan is literally a meeting place: the tree’s expansive crown and aerial roots create a natural hall where assemblies, dispute resolution and ritual gather. The banyan’s figure in Indian imagination is of strength and longevity; it is the tree of shelter and sustenance, a botanical analogue to the idea of unity.

These two trees — one temperate, one tropical; one compactly urban, the other sprawlingly communal — share surprising contemporary common ground in policy and technology. Nations are no longer content with symbolic planting or ceremonial dedications alone; they have moved to scale and to data. India’s forest statistics, as often cited in policy discussions, place the country’s forest and tree cover in the order of many tens of millions of hectares (Indian State of Forest Report). Globally, forests continue to occupy roughly a third of the land surface — a baseline figure reiterated in contemporary policy proposals. Such numbers supply both the scale for action and the urgency for monitoring.

Technology — machine learning, satellite observation, and drones — now enters this arena not as novelty but as necessity. Recent pedagogical and policy discussions have argued for AI-enabled systems to consolidate fractured forestry data, to provide near real-time alerts on illegal activity, and to guide targeted replanting and restoration. The proposition is straightforward: where human resource and institutional fragmentation impede enforcement, analytics and remote sensing can identify hotspots of loss, direct ground teams, and reduce lag between detection and action. Academic and teaching exemplars stress, however, that technological systems must be matched by governance will: data without boots on the ground will not save a tree.

Official attention follows. Government releases and high-level statements have underscored environmental stewardship as part of statecraft; contemporary speeches and press notes reiterate the theme of development in tandem with conservation. Whether the object is a lípa planted to mark an independence anniversary or a banyan planted under a village initiative, the political frame is now one where planting and protection are both civic acts and matters of record.

What, finally, do these parallels teach? First, that national trees are not merely symbols hung in civic rhetoric: they are social actors — places where histories are made, where local identities gather, and where memory is materially kept. Second, that the science of trees sits uneasily beside the poetry of trees: claims about longevity, medicinal efficacy or exact counts of plantings are often entangled with folklore and local pride; prudent writing must therefore keep folklore and field data in conversation rather than collapsing one into the other. Third, that twenty-first century conservation will be hybrid: it will combine municipal planting programmes and cultural stewardship with remote sensing, AI analytics and cross-institutional data sharing.

The lípa and the banyan thus stand as complementary exemplars. Be it in Prague's city squares or in the Czech villages, the lípa remains a civic icon, a marker of memory and identity; in India the banyan remains the village’s heart, a living parliament under which life is ordered. Both demand and are beginning to receive new kinds of care at various levels to include legal protection, municipal inventories, technological surveillance and, above all, public attention. To protect them is to preserve not only wood and leaf but the social forms and rituals that cluster beneath their shade.

Sources

https://tinyurl.com/28r9w4cr

https://tinyurl.com/2d2y7jpk

https://tinyurl.com/2ddod5g3

https://tinyurl.com/255o4bnf

https://tinyurl.com/2y4znrzs

https://tinyurl.com/29zjyzd9

https://tinyurl.com/27259ge2

https://tinyurl.com/2a5kdrdv

https://tinyurl.com/27mh8ux3

https://tinyurl.com/2xu8b6dj

https://tinyurl.com/2xu8b6dj