Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

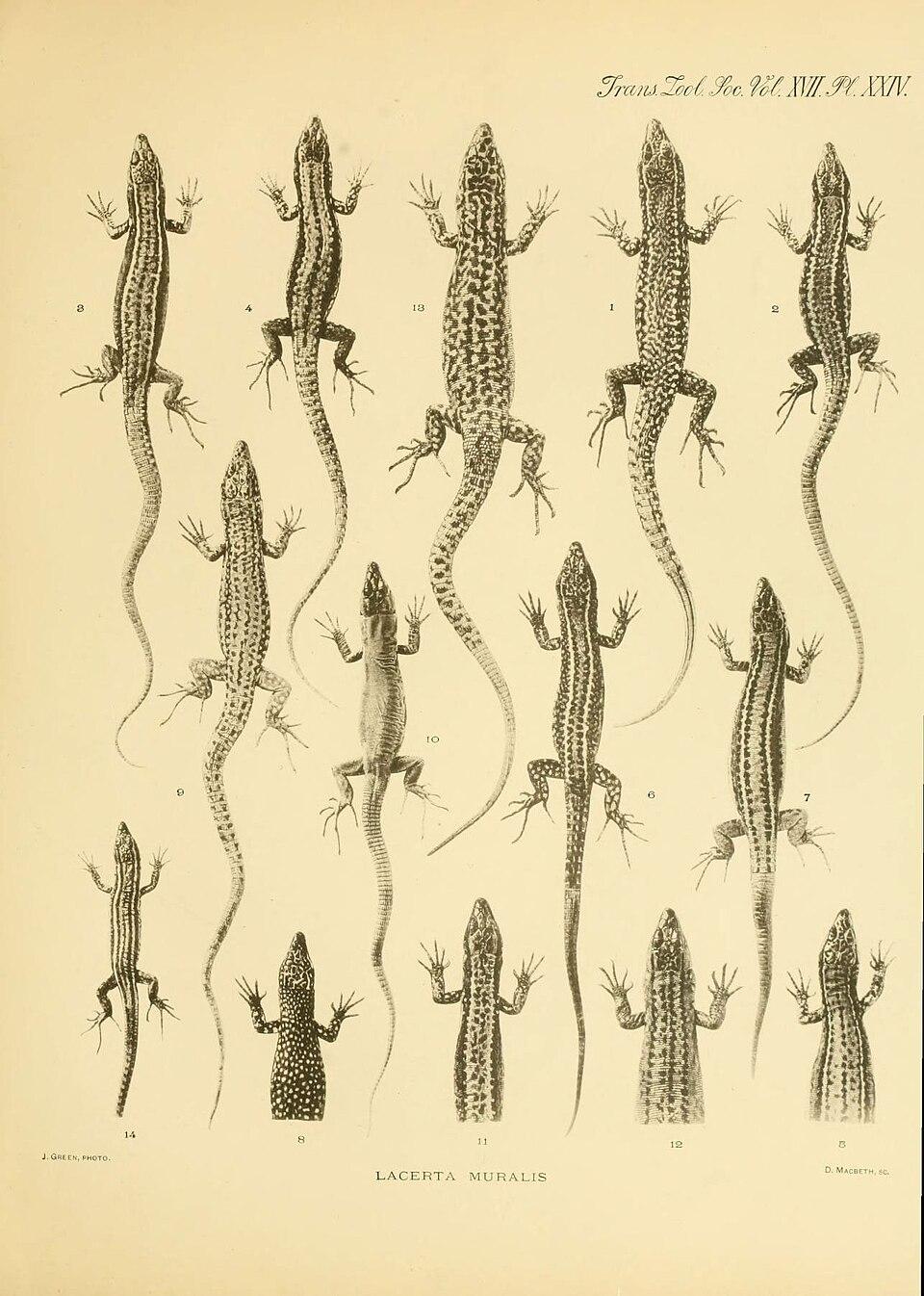

Because of their behavior and small size, lizards live close to people. They inhabit the cracks in garden walls, the sunlit stones of old ruins, the margins of paddy fields and the thorny hedges that separate one smallholding from another. They are ordinary enough to be overlooked, and curious enough, in form, behaviour and life cycle, to draw the attention of naturalists. Across two very different geographies, the Czech Republic and India, recent field reports and conservation notes remind us of two linked truths: that lizards do quiet but vital ecological work, and that their fortunes depend on the tiny features of the landscape which we can easily lose.

A brief natural history note is useful. Lizards are a broadly diverse group of reptiles; some are tree-dwelling geckos, others rock-clinging lizards, and many feed mainly on insects. Their life cycles and activity patterns are tightly tied to local climate and habitat structure, and because of their small home ranges they often respond quickly to local environmental change. For gardeners and farmers this is good news: where lizards persist pest insects are kept in check; where they disappear, other signs of a simpler, less healthy ecosystem soon follow.

Czechia’s stones, northern surprises

On soils in the Czech Republic long-known species such as the European green lizard and various wall lizards occupy warm, open habitats — limestone outcrops, old masonry and sunlit embankments — and are familiar to anyone who spends time outdoors. Regional field guides and checklists name these species among the most visible representatives of the country’s reptile and amphibian life.

Yet the record from the Czech Republic also contains surprises. Reports noted a Balkan wall lizard population well to the north of its previously understood range, a discovery that either records a recent northward expansion or uncovers a relict population that had been overlooked for decades. Finds at the edge of a species’ range matter: populations at the margin of a species’ distribution often carry distinct genetic variants and adaptations, and they change how we decide what and where we must protect. This is a reminder that even in a small country we should not assume we know where a species begins or ends; careful surveying can rewrite those boundaries.

Zoos and husbandry

Conservation in the Czech Republic is not only a matter of field lists and range notes. Zoos have played a practical role in reptile and amphibian work, developing husbandry techniques and maintaining insurance populations. A zoo announced a notable captive success: the birth of a rare monitor lizard under controlled conditions, an event that advances the breeding knowledge so necessary for any potential reintroduction effort. Captive, off-site work like this serves two linked purposes: it safeguards genetic material when wild populations are precarious and it builds the craft of care that conservationists may need in an emergency.

India’s scale and conservation practice

Move east, and the story broadens. India’s reptile fauna is very diverse. From riverine crocodilians to small skinks and agamid lizards, the country supports a great variety of groups, many of them found only in small areas. Alongside institutions, individuals have shaped modern conservation practice there. Their work — founding a crocodile conservation centre, training local communities and establishing cooperative, livelihood-linked models such as a cooperative of snake catchers — shows how conservation in India has often been practical, local and socially embedded. This approach is a clear lesson in combining fieldwork with community engagement, turning fear into stewardship.

Yet India’s agricultural and developmental landscape places severe pressures on reptile life. A considered review argues that farmland reptiles and amphibians are especially vulnerable to agricultural intensification. Hedges, field margins, seasonal ponds and uncultivated patches, the small habitats that sustain reptiles and amphibians, are often the first features to be lost when farms are modernised. The review argues, with data and practical advice, that simple, low-cost measures, retaining hedges, conserving ponds, reducing pesticide use, can make farmland friendlier to reptiles and amphibians without threatening productivity. Put bluntly: conservation for reptiles in India begins in the margins of fields.

Citizen networks and the data commons

Across India the bringing together of sightings and photographs into national websites has become a powerful tool. National online resources that bring together species accounts and images turn casual observations into confirmed records and help prioritise places for protection. In a landscape where many species occur in tiny, isolated pockets, a single confirmed locality can change conservation decisions. Citizen science thus matters as both an early warning system and a mapping tool, a way for ordinary people to contribute directly to the record that conservationists use.

Gardens, fields and small things that matter

It is worth pausing on the humble garden. Gardening guides emphasise the ecological services lizards provide in domestic and cultivated spaces: they consume pests, require little space, and signal the presence or absence of harmful chemicals. Encouraging lizards in home gardens is straightforward — retain rocks and leaf litter, reduce pesticide use, plant native species — and the benefit is immediate. Such local, low-cost measures reconnect the scale of everyday life with species-level conservation.

A common lesson from two places

What links a northward wall lizard in the Czech Republic and India’s plea for farmland hedges is not a single method but a shared attention to small things. At a zoo the careful captive breeding and the new range records both expand our knowledge of what is possible; in India community-based conservation and an analysis of reptiles and amphibians on farmland point to what is necessary. Both contexts ask for patient observation, keeping small habitats, and an acceptance that conservation often succeeds at the scale of a garden wall, a seasonal pond, a patch of scrub — not only at the scale of reserves and announcements.

If conservation is to persist it must be locally minded. Protect the stone ledge, spare the hedge, retain the pond; care for the small things and lizards will continue, in their common, remarkable way, to remind us of what the landscape once was and what it might yet become.

Sources:

https://tinyurl.com/6956v33

https://tinyurl.com/2yhkdtjk

https://tinyurl.com/2a28ws25

https://tinyurl.com/2yalhzso

https://tinyurl.com/2dkdlr4l

https://tinyurl.com/2y8nsohz

https://tinyurl.com/2dfxyreh

https://tinyurl.com/22jgn4mh