Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

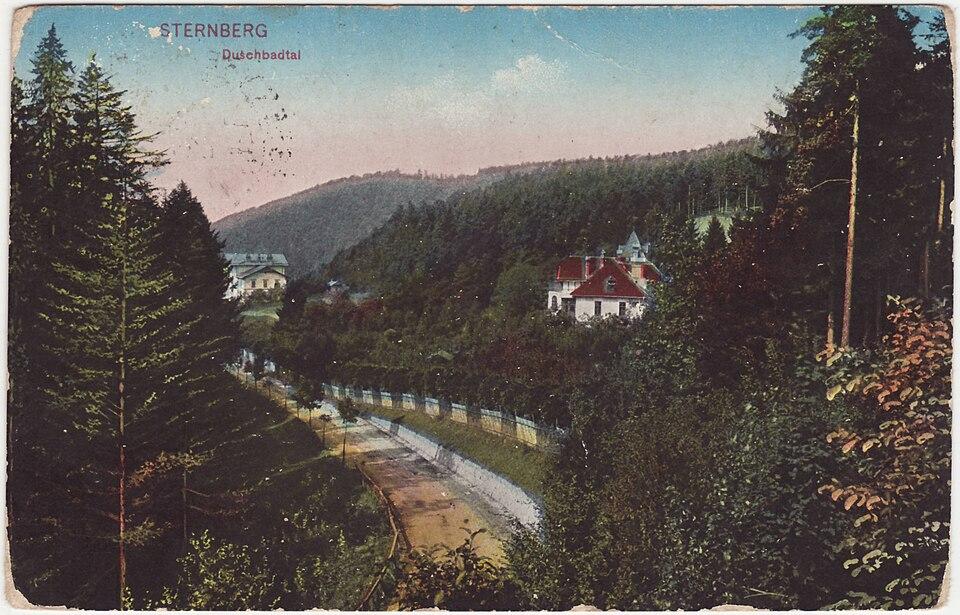

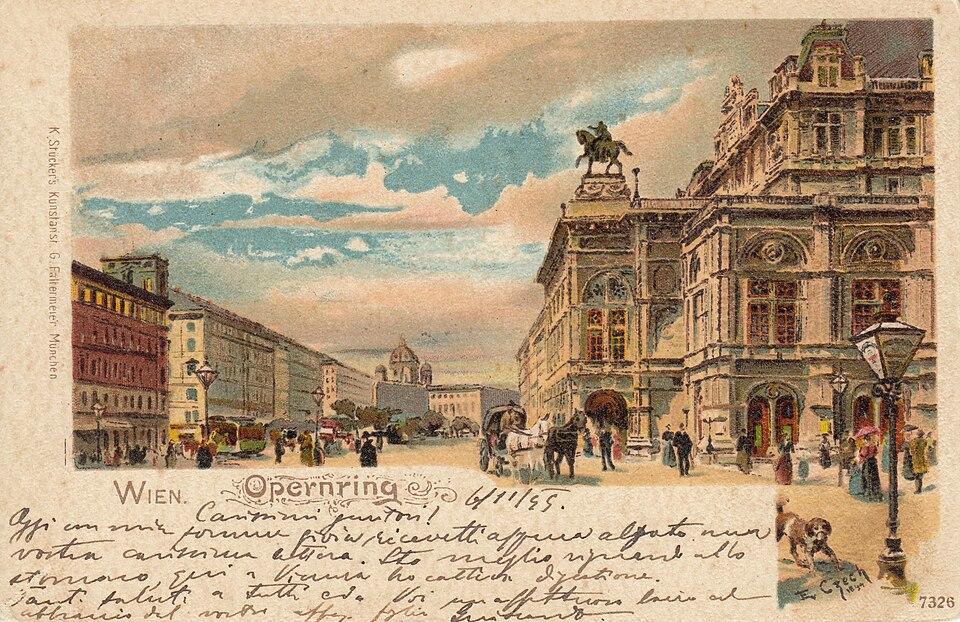

There are objects that quietly keep time, not in the slow sweep of a clock but in the small traces of human exchange. The picture postcard is one such object: a rectangular card that carries an image and a small note of handwriting and, in doing so, condenses travel, taste and a moment of social life. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century networks of empire and curiosity, picture postcards functioned as art, advertisement and a cultural snapshot all at once. Picture Postcards of India conveyed to Europeans what India looked like, and they carried Indian scenes back into foreign drawing rooms. Those same cards, carefully collected, catalogued and now digitized, have become a bridge between an older habit of collecting and exchange and a new, digital one.

The history is, in essence, straightforward. In India the modern postal infrastructure developed over a century; picture postcards were formally introduced into postal services in the late nineteenth century (1896), and from that moment images and short notes joined the ordinary postal business of communication between people across the globe. Collecting these views soon became a habit for travellers and residents alike; in Europe and in colonial cities, picture postcards captured cityscapes, public buildings, transportation, occupations and scenes of everyday life — a visual archive assembled one card at a time.

A single human story brings this clearer than any general statement. Ratnesh and Sangeeta Mathur, who lived in the Czech Republic before returning to India, found thousands of Raj-era postcards in Central European antiquarian markets. These had been sent by Europeans living in India to their friends and family in Europe. The postcard collection of the Mathurs, now running into the thousands and forming the basis of a published book, is precisely the sort of dispersed archive that picture postcards quietly create — images of growing urban Indian centres during the Raj era, of canals and palaces, of the cultural life in India, that otherwise might have remained scattered in personal albums in travellers' homes. The Mathurs’ work in cataloguing and digitizing their finds shows how postcards have been rescued from ephemera and raised into curated history, a study in sociology, urban planning and the colonial era.

But why did picture postcards matter then, and why should they matter now? The answers sit on two levels. Practically, postcards were cheap, easy to carry and quick to send and communicate with. They were the nineteenth-century equivalent of instagram - containing an image and a short note. Culturally, they created a shared set of images about places: how Bombay presented itself to outsiders, how a European collector imagined “India.” These card images became a shared set of views that helped shape memory and identity for both sender and recipient. The Mathurs’ decision to assemble and publish a book of these cards is, in itself, an act of cultural retrieval: the cards are now sources for historians, artists, urban planners, sociologists and citizens who want to see how people and places once looked.

Fast forward to the present and the medium changes but the impulses do not. Digitization keeps the picture postcard’s key qualities — easy to carry, quick to share, and image-based — while adding to the qualities of scale, reach and search. Collections that once exchanged hands at fairs can be photographed, tagged and made discoverable; public audiences that could never visit a Prague antiquarian shop can now browse that postally used postcard from their phone. At the same time, modern digital communications tools — AI-powered content production, messenger commerce, augmented reality previews and highly personalized channels — are changing how memory and exchange work: messaging apps replace the physical postman, user-generated content replaces the single publisher’s image, and AI helps scale captioning, categorization and even image restoration. These are not merely technical advances; they alter which images travel (selection), how they are curated and who participates in the conversation.

The Czech angle fits this pattern: Europeans and people in Czechia who once traded in postcards now also use digital platforms to collect, share and research. Studies of Czech students’ travel behavior show that social media is integral to the travel process — used for planning, for sharing impressions and for collecting opinions while abroad, with many relying on major social platforms when travelling. In short, the social practice that once required a postal network now often unfolds in feeds and stories. That continuity in behavior — movement, images and exchange — is what connects the old card table to today’s timeline.

India’s story runs alongside this. The picture postcard era left archival traces of Indian towns and cities; today India’s enormous population, its vibrant street life and its expanding internet footprint mean that image-based exchange has exploded in form and scale. Platforms and messenger apps popular in India support commerce (payments via chat) and amplify user-generated imagery (reviews, short video), so the small, private act of sending a view has become a public act that can be monetized, archived and recycled. The Mathurs’ attempt to share their collection in their book, therefore is a clear example of a larger movement: citizens and institutions are transforming private holdings into public collections, and digital tools are making that process faster and more participatory.

There is an irony and a practical lesson. Picture Postcards once functioned as informal documentary evidence — a street scene, a building façade, a traditional costume of the locals — and they have proved invaluable to historians precisely because they were mass produced, widely distributed and intimately annotated. Digital exchange offers the same documentary value with far greater volume, but that very abundance complicates curation: which images matter, who verifies origin, and how are records preserved? Here the archive work of collectors and the capabilities of AI come together: digitization needs human judgement in selection and research; AI offers search, auto-tagging and restoration; both are required if the visual history of places and people is to remain understandable for the future.

In the end the story is less technological than human. Whether on a thick picture postcard with a postage stamp and a smudged hand mark or in a curated online gallery with machine-generated captions, images travel because people want to share, to remember and to exchange. The Czech-Indian thread of postcards — from flea markets in Prague to collection rooms in Mumbai, from printed caption to metadata — is a reminder that communication forms change but their social purpose does not: which is to carry place views, to carry a greeting, to carry memory. The challenge now is practical: to use digital tools to make those memories visible, reliable and shared, without erasing the small, intimate traces that made the postcard more than a commodity, a social object and a doorway into other lives.

Sources:

https://tinyurl.com/255ftrv7

https://tinyurl.com/2d5lwksx

https://tinyurl.com/299dra4f

https://tinyurl.com/29hdowox

https://tinyurl.com/2xau336c

https://tinyurl.com/ycsw28jm

https://tinyurl.com/23hbdbgg

https://tinyurl.com/27hy628e