Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

By the time libraries began to catalogue their holdings in the modern sense, pages and leaves of manuscripts had already carried whole worlds in their fold. Manuscripts, whether as books made in medieval scriptoria, palm-leaf bundles inscribed across South Asia, or fragile Arabic volumes preserved in monasteries, are not merely objects of curiosity; they are repositories of language, history, philosophy, technique and memory. In two different ways, the National Library in Prague and the National Mission for Manuscripts in India show how knowledge and its curation these days moves from shelves to servers, and from careful handwork to machine learning, a continuity of care that connects stone, leaf and byte.

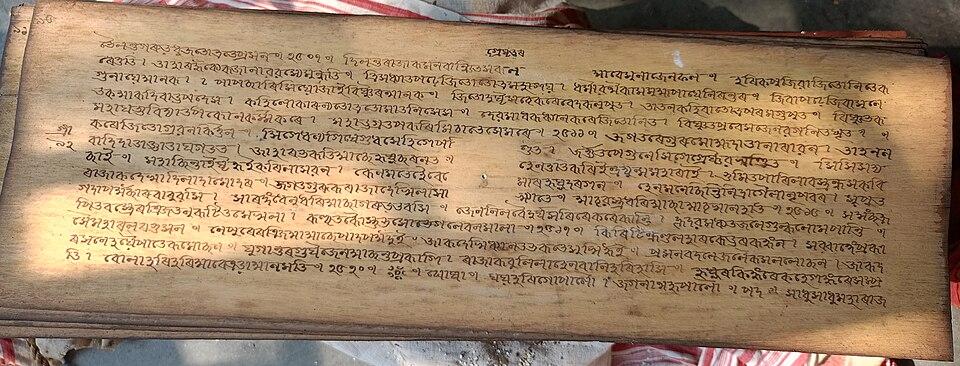

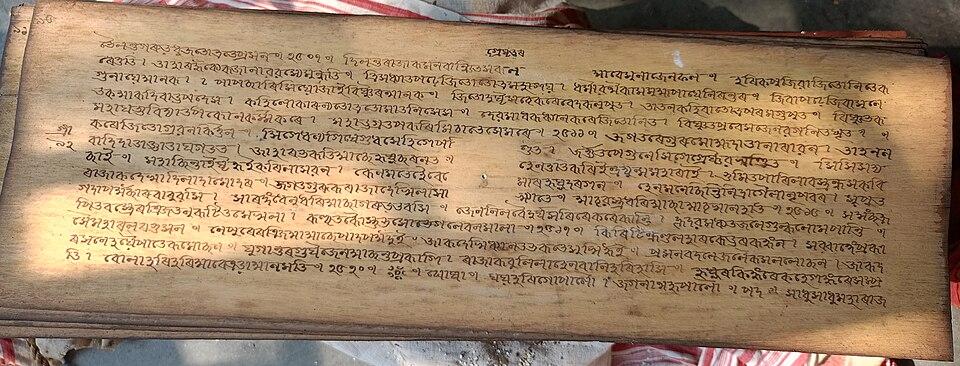

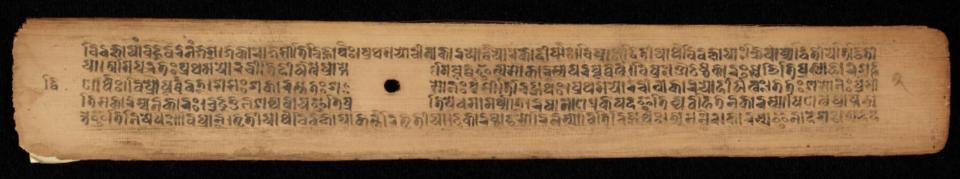

Prague’s principal library collections tell one half of that story in quiet, book-lined rooms. The National Library of the Czech Republic preserves a broad manuscript collection, roughly fourteen thousand units that range from classical codices to Asian holdings, and it houses a collection of Asian manuscripts of about 1,200 volumes, more than half of which are Indian manuscripts written on palm leaves. These items entered the collections over many centuries: as gifts, purchases and the transfers that followed the reorganisation of monastic and university libraries in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The library’s cataloguing and digitisation programmes, part of long-running professional activity in the Department of Manuscripts and Early Printed Books, present these palm-leaf bundles not as exotic objects but as records that connect Prague’s reading rooms to South Asian textual cultures.

That Czech stewardship is, in some respects, a result of historical collecting practices: acquisitions in the early twentieth century and later day consolidation brought Indian palm-leaf manuscripts into a Central European archive where they became part of a multilingual, multi-script collection, Greek papyri beside South Asian palm leaves, medieval codices alongside Jesuit collections. These items are catalogued with a librarian’s precision (shelf marks, provenances, language sections) and conserved according to institutional routines developed over decades. Such provenance details matter: they allow researchers to trace how texts travel, how knowledge moves with people and politics, and how a palm-leaf bundle from the Indian subcontinent becomes a subject of study in a Prague reading room.

But the other half of the story unfolds in India in a different way. Where Prague protects and describes, India is engaged in scale: the National Mission for Manuscripts, recently restructured and renamed as the ‘Gyan Bharatam Mission’ for the period 2024–31, has been tasked with surveying, conserving and digitizing an enormous manuscript heritage. The Mission’s publicly stated figures are striking: over 5.2 million manuscripts have now been documented across repositories nationally; roughly 3.5 lakh manuscripts (covering some 3.5 crore folios) have been digitized; and more than 1,35,000 manuscripts have been uploaded to the web portal (with around 76,000 available for free public access). The programme’s budget and structure, a central government scheme with multi-year allocation, signal a deliberate pivot from isolated conservation projects to a national, digital programme.

Digitization, however, is not simple replication; it is a series of choices about resolution, metadata, access and community. India’s Mission emphasises survey and registration, scientific conservation, publication, capacity building and outreach, a framework designed to make manuscripts usable as well as preserved. The country’s pilot digitisation projects, which date back to the early 2000s, have shown how the technical task (scanning, storage, catalogue) must be accompanied by training in paleography and manuscript studies if the digital copies are to be intelligible to scholars. The National Digital Manuscripts Library aims to be both a repository and a research infrastructure: a place where folios are not only scanned but described, edited and set into scholarly conversation.

Preservation and digitization meet an even more new frontier when computers are used to read what human eyes struggle to decipher. Ancient and regional scripts, mixed scripts, faded ink and shorthand abbreviations present a difficult set of pattern recognition problems. Some Indian institutions are now tackling these with machine learning. The Asiatic Society in Kolkata, for example, has started Project Vidhvanika to digitize its holdings (more than 52,000 rare manuscripts) and to develop machine learning models that can assist transcription and reading. Working alongside India’s Centre for Development of Advanced Computing, the Society is building language models for historical scripts; early results are modest in accuracy but promising as an assistive tool, with model performance improving as annotated corpora grows. The administrators involved estimate that current prototype accuracy requires substantial further training; the project is very much an iterative collaboration between paleographers and coders.

The computational turn is especially intriguing in light of enduring uncertainties about scripts that pre-date any living readers. The Indus script, for instance, remains undeciphered; it is a complex set of some 400 or so standardized signs used in short sequences during the Mature Harappan period (c. 2600–2500 BCE), and despite a century of effort it resists a full phonetic reading. Computer-assisted studies and the work of several twentieth-century teams (including notable Russian and Finnish researchers) have yielded hypotheses, including Dravidian connections proposed by some computational analyses, but the absence of long texts and obvious bilingual parallels makes full decipherment unlikely without new evidence. Machine learning may help chart patterns and probabilities, yet the Indus case also reminds us that algorithms are tools, not miracles: they need corpora, annotations and cross-disciplinary interpretation to matter and yield results.

Read together, these institutional stories, Prague’s careful catalogues and India’s digital surge, the Asiatic Society’s models and the continuing mystery of Harappan signs, show a common lesson. Preservation is neither purely about old things nor purely technical; it is a practice that must combine careful details about provenance conservation, transparent cataloguing and the careful use of computing to open texts, not to close interpretive possibilities. The Czechia collections show why provenance and classification still matter; India’s national mission shows how scale and accessibility can be pursued without surrendering scholarly rigor; and AI projects show how new tools may reduce labour or suggest readings while leaving value judgments to human specialists.

There is, finally, an ethical and political dimension that both countries confront. Manuscripts carry contested histories, of colonial flows, private collecting and public transfer, and of scripts that have been marginalized or valued, and digitization raises questions about who controls access, how texts are contextualised, and whether communities that produced or transmitted manuscript traditions are included in the stewardship. The work that lies ahead, whether in Prague’s reading rooms or in India’s digitisation labs, will be judged not by terabytes stored but by whether these texts become intelligible, usable and, above all, accountable to the scholars and communities who claim them.

Sources:

https://tinyurl.com/2n2d2k7j

https://tinyurl.com/2n2d2k7j

https://tinyurl.com/2bpfys9u

https://tinyurl.com/2adp7lvc

https://tinyurl.com/2a43uh8f

https://tinyurl.com/2bf925xd

https://tinyurl.com/2d2gv5wk

https://tinyurl.com/2yxtk34u