Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

When archaeologists label a whole cultural horizon by one single practice, it is because that practice marked people's lives in a way that mattered, materially, ritually and socially. The Urnfield tradition of Central Europe, named for the routine of cremating the dead and burying their ashes in urns in open fields, is one such horizon which was prevalant roughly around 1300–750 BCE within the Late Bronze Age. Across the same centuries, South Asia had cultivated another powerful funerary pattern called “Antyesti”, which referred to the Vedic and later Hindu last rites upon death, that normally involved a carefully staged cremation ritual, and the placing or immersion of ashes in sacred waters (in the River Ganga especially). Placed side by side, these two practices show how human communities in different landscapes used fire and receptacles (urns or rivers) to organise memory, status and the return of bodies to elemental order.

The Urnfield world: cremation, fortresses and bronze

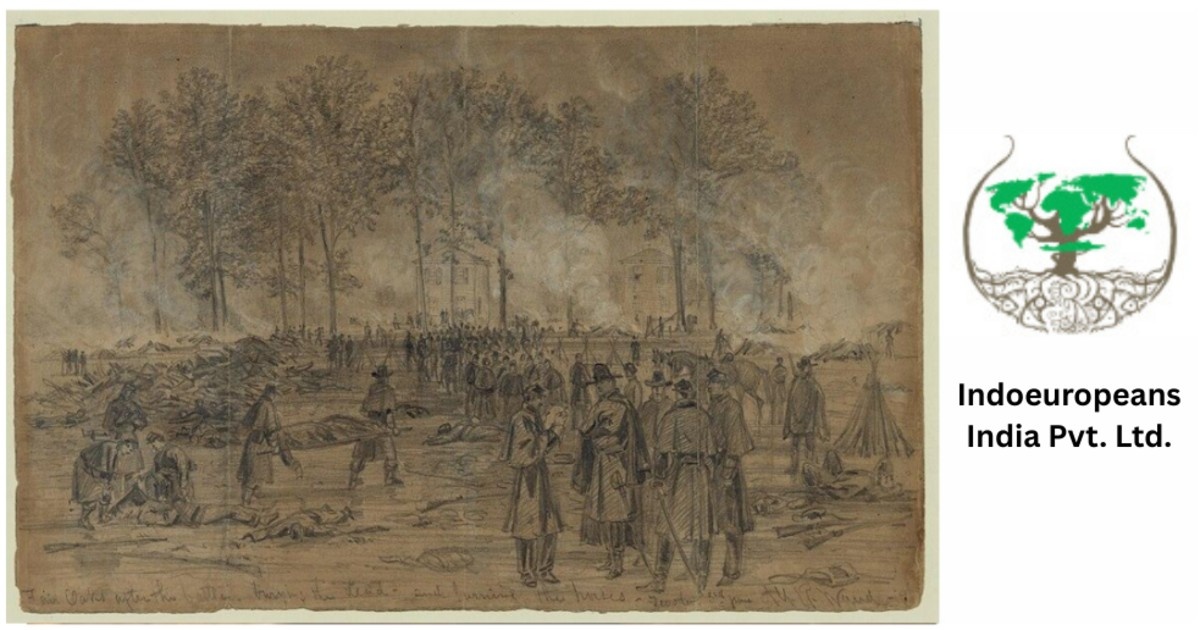

Archaeology's portrait of the Urnfield tradition is a landscape of embanked hilltops, fortified settlements, metal workshops and, importantly, fields of urns for ashes. The culture's name is literal: in many regions people routinely cremated the dead, placed the ashes in ceramic urns, and buried those urns in cemeteries of dispersed fields, the "urn fields" which give the tradition its label. Fortified hilltop settlements, with dry-stone or timber ramparts and river-bend enclosures, become common in this period, and metalworking (sheet-bronze techniques, moulds, axe and dagger manufacture) is often concentrated in these well defended city centres. The archaeological picture is therefore twofold: the appearance of technologies that require specialised workshops (metallurgy, moulding) and the emergence of funerary practices that show social differences.

Material signals of status accompany these burial practices. Urnfield cemeteries are not uniformly modest: some graves are accompanied by rich grave-goods, weapons and prestige objects (and elsewhere, distinct "upper-class" inhumations remain). Across Central Europe archaeologists find hoards of decorated vessels and artefact types that circulated widely, evidence that bronze, prestige goods and standardised forms operated as a social technology that bound elites, workshops and long-distance exchange. Recent fieldwork in the Czech Republic, including large burial grounds and micro-studies such as the Mikulovice excavation, has added texture to this portrait. Richly furnished burials (an amber necklace of hundreds of beads, food containers placed with bones) and biological analyses (isotope and DNA work) show complexity of diet, mobility and status at the turn of the 2nd millennium BCE.

Urns, public memory and technological craft

The urn itself is a compact cultural object. It receives ash and bone, it can be decorated or plain, it is portable prior to burial and durable afterwards; it therefore serves multiple needs: practical, symbolic and memorial. Archaeological narratives have long read their decoration and associated offerings as social statements: an urn field with patterned pottery and goods indicates a community's ritual investments as surely as a princely barrow does. Importantly, cremation as a funerary strategy is not unique to the Urnfield horizon: archaeologists note cremations in earlier Mesolithic and Neolithic contexts in northern Europe and elsewhere, and the precise origin and spread of cremation rites is complex, with visible regional variations. That complexity matters when we compare Urnfield cremation with ritual systems in other parts of Eurasia.

Antyesti and the river-rites: The five elements and spiritual release

In a different context, but with some formal echoes, "Antyesti" in the Indian textual and ritual tradition frames death as a transition in which the body is returned to the five elements (earth, water, fire, air, space) and the soul is released. Vedic texts supply the metaphors and some ritual lines that support later Hindu funerary practice; Antyesti (literally meaning "the last sacrifice") typically involves washing and wrapping the body, a ritual procession to a cremation ground on the banks of a river, the lighting of the pyre by a chief mourner, recited hymns and post-cremation rites to finally deposit the ashes into the river or sea. The philosophical logic is explicit: cremation is both purification and a sacred means by which the body is returned to the cosmos.

Why the river? For many Hindus the River Ganga plays a special role as a purifier and liberator; the immersion of the asthī (ashes) in the Ganga is believed to cleanse impurities and assist in the soul's onward journey toward moksha. Popular narratives and devotional commentaries explain the legend of Bhagirathi or the descent of the river Ganga onto Earth, and the metaphysical reasons for this practice. Contemporary writers and popular media reiterate the image of Gangajal as a solvent of sin and a means of release. At the practical level, rivers have long functioned as places where communities congregate, perform rites and to signify the passage from domestic, earthly life into larger cosmological orders.

Parallels, differences and cautious inferences

Put together, the Urnfield and Antyesti practices share certain features: both use fire to transform the body, both convert the remains into specific, socially managed materials (urns; collected ashes), and both place the act within ritual systems that regulate access, status and memory. Yet the differences are important. Urn burial fixes the remains in a durable place on a landscape (an urn field or burial plot). Vedic practice of Antyesti culminates in dispersal of the mortal remains through immersion in flowing water, as a metaphorical and literal return to a cosmological flow. The archaeological record of Urnfield in the form of objects, urns and grave goods, thus emphasises permanence and localised memorialisation. On the other hand the textual record of Antyesti emphasises purification, sacrament and the trancendence of the soul.

What about the Indo-European links?

The temptation to draw a straight line from Central European cremation rites to Indian Vedic traditions on the basis of shared Indo-European ancestry must be resisted or at least qualified. The Urnfield rituals have been traced by some scholars to later Indo-European language groups as well (and cremation does appear in several early Eurasian contexts), but the archaeological data also show independent and earlier instances of cremation in northern and central Europe. In short, similar rituals may reflect both genealogical transmission in some cases and independent development of similar rituals in other cases, as societies everywhere, when faced with death, devised practical and symbolic solutions that often make similar use of fire, urns and water.

Sources:

https://tinyurl.com/28alng54

https://tinyurl.com/2685o2km

https://tinyurl.com/24o7jvs6

https://tinyurl.com/22l6uwo4

https://tinyurl.com/23jw4nkz

https://tinyurl.com/2aow222f

https://tinyurl.com/2aow222f

https://tinyurl.com/24dlq5qo

https://tinyurl.com/26bakgwo