Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

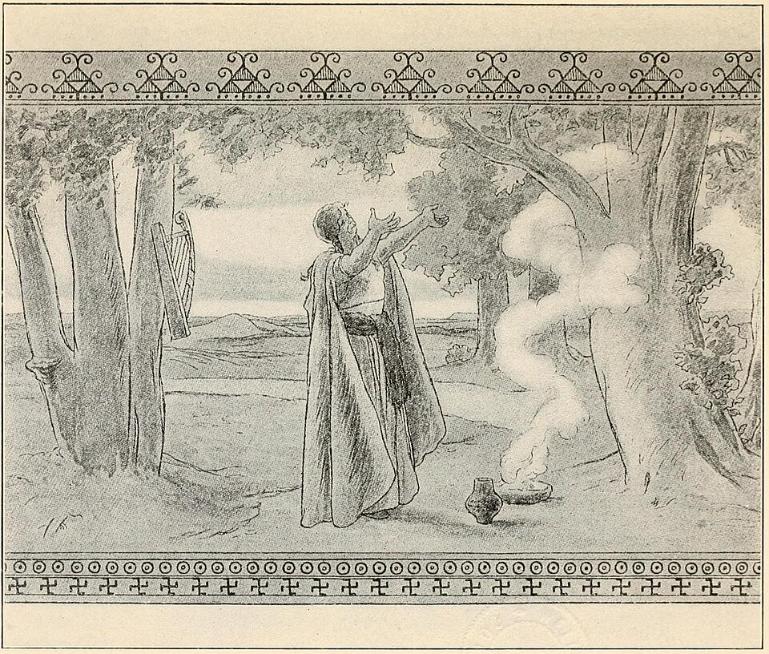

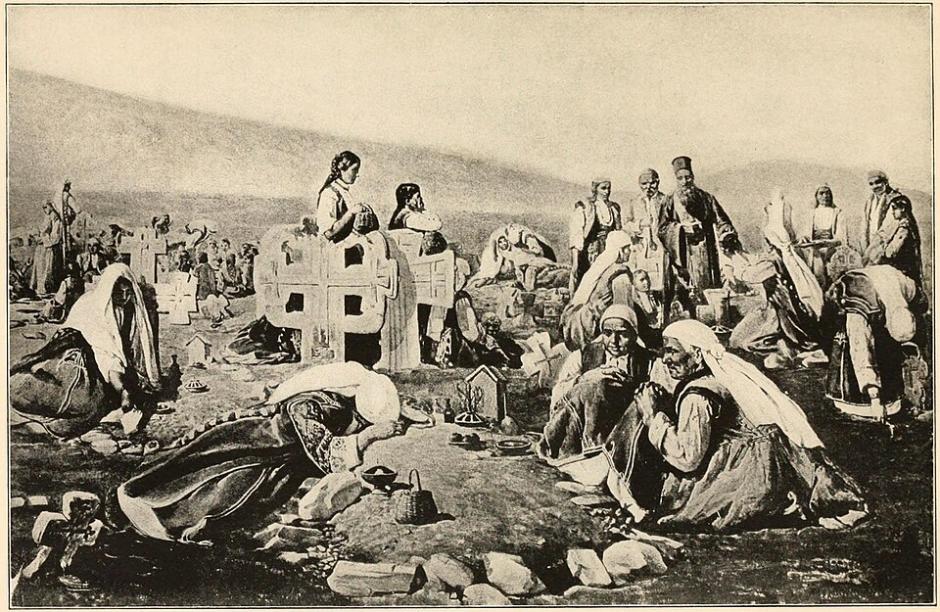

By the period scholars sometimes call the "Age of Religion" (roughly 600 BCE to 300 CE), communities across Eurasia had already placed ritual at the centre of social life. They organised calendars by fire rituals and festivals, named deities that governed harvest and storm, and set patterns for how the living should respond to nature and material loss. In the lands that would later become the Czech Republic, folk bonfires and spring rites (later consolidated into what is now called pálení čarodějnic or Valpuržina noc) preserved echoes of pre-Christian seasonal religion. In South Asia as well, burning rituals such as Holika Dahan and the larger system of Vedic funerary rites made fire itself a medium of purification, regeneration and social order. Read together, these practices show how fire shaped time: turning winter into spring, death into renewal, and individual grief into a communal ritual.

Spring bonfires in the Czech Republic : banishing winter, conjuring spring

Across Bohemian villages the night of 30 April–1 May has for generations been marked by great bonfires and communal celebration. Known popularly today as the "burning of the witches" (Valpuržina noc), the custom symbolizes the expulsion of winter's dark and cold days, and the welcoming of spring / summer's fertility and burst of life. Villagers light pyres, gather to dance, jump across embers and share food and drink. Beer figures regularly in modern descriptions of this continuing festival. Contemporary accounts stress the celebration's lively social life, with music, roasted sausages and folk gatherings, and its endurance as a local rite even amid modern urban regulations and climate change.

Scholars who study the custom are cautious about their origin stories. While popular narratives often link Valpuržina noc to indigenous pagan rites of renewal, historical work suggests that the event as practised today crystallised under layered influences, including medieval Christian calendars, Germanic Walpurgis traditions and parallels with the Gaelic Beltane (and even occasional comparisons with Jewish Lag BaOmer are made). Where documentary evidence is thin, the ritual's persistence is telling: a spring bonfire whose popularity may rise and fall with political regimes nonetheless reappears as a communal way of marking seasonal transitions. Local records show that the custom was banned at times, in the nineteenth century and during wartime, yet it resurfaced as a public celebration in the modern era.

Fire and purification Rituals in South Asia: Holika Dahan as a Spring Festival

On a different cultural current, Holika Dahan, the bonfire on the eve of the Hindu Festival of Holi, presents a mythic story of deliverance. The story of the devotee Prahlad and the demoness Holika (who is burned on a pyre while Prahlad ecapes all fire injuries) is retold across India as an emblem of righteousness triumphing over evil. The bonfire is symbolic : it marks the seasonal turn toward spring, it cleanses through sacrificial flame, and it provides a forum and space for community gathering. In many regions the ash is preserved and scattered; in others the embers are leapt over in acts of symbolic purification. Holika Dahan is thus both a moral tale and a calendar marker that aligns farming seasons with communal memory.

Beyond the story itself, Holika's ritual logic rests on a Vedic and post-Vedic framework: fire as agent of transformation, the pyre as a place where material and moral orders meet, and collective rites that reaffirm social bonds. The festival's symbols and practices have proven endearing and have survuved the sands of time. Even as communities become more secular or migrate to other regions, the Holika bonfire remains a point of cultural continuity, reworked in village squares and city parks alike.

Beyond the story itself, Holika's ritual logic rests on a Vedic and post-Vedic framework: fire as agent of transformation, the pyre as a place where material and moral orders meet, and collective rites that reaffirm social bonds. The festival's symbols and practices have proven endearing and have survuved the sands of time. Even as communities become more secular or migrate to other regions, the Holika bonfire remains a point of cultural continuity, reworked in village squares and city parks alike.

Parallels, continuities and cautious comparison

The comparison of Valpuržina noc and Holika Dahan brings certain striking parallels into view. Both are spring rituals that use fire to mark transition; both bring communities together around food and drink; both enact purification and renewal through a visible, public spectacle; and both have long local traditions that scholars and popular commentators sometimes trace to pre-Christian or pre-classical antecedents. These shared features, bonfire as rite of passage, flame as purifier, ceremony as anchor of communal identity, are less surprising than instructive: human societies repeatedly translate seasonal uncertainty into ritual certainty.

Yet important differences shape the meaning each tradition takes on. In Czech Republic's case, the bonfire custom often bears the imprint of a mixing of traditions (folk practice layered over Christian calendars and medieval lore), and the practice sometimes emphasises expulsion (of witches or winter), a public cleansing of perceived harmful forces. In India, Holika Dahan rests on a mythic narrative that ties personal piety to cosmic justice and often integrates the rite into broader Vedic funerary and sacrificial frameworks (where fire mediates life, death and rebirth). The Czech bonfire tends to fix memory in place: a local field, a village square; while the Indian ritual points both to local community and to a sacred geography across India, notably when immersion of ashes or other rites link them to rivers or pilgrimage routes.

Religion and social formation: India, 600 BCE–300 CE (and aftermath)

If the Czech lands retained folk pagan currents during the centuries in question, India witnessed major structural religious transformations between 600 BCE and the early centuries of the CE. The period saw the rise and consolidation of non-orthodox movements (Buddhism and Jainism), the administrative and ritual innovations of empires such as the Maurya, and later cultural combinations that would set the stage for classical Hindu forms. By the early centuries CE literary and ritual traditions, including the epic corpus and refined sacrificial systems, had become central to social identity and statecraft. Scholarly overviews of Indian chronology place these developments in a timeline that leads, in a subsequent phase, to the classical flowering of the Gupta age.

The Gupta era (commonly dated c. 319–540 CE) is often invoked in comparisons for its role in standardising texts and rituals, the period in which the epic narratives assumed lasting cultural centrality and regional courtly patronage strengthened canonical arts and religion. Though the Guptas fall slightly after the 600 BCE–300 CE window, their consolidation helps explain how earlier religious ferment was later institutionalised and widely disseminated across South Asia.

Indo-European echoes and convergent ritual evolution

Scholars sometimes point to broad Indo-European motifs, sun, rain, storm and wind gods, fertility cycles, and spring fire rites, as a useful comparative vocabulary. Valpuržina noc's late medieval and Germanic resonances, and the widespread nature of spring bonfires across Europe, suggest some shared cultural patterns; yet scholars caution that similar rituals can arise independently wherever seasonal risk and agricultural cycles demand social regulation. In short, parallels may reflect deep genealogies in some instances and independent development in others; both possibilities are compatible with the archaeological and textual evidence.

A modest concluding thought

If there is a common lesson in the fires that lit the Czech plains in spring, and the pyres that warmed Indian riverbanks, it is this: ritual is as much a technology of social life as metallurgy or irrigation, a means by which communities order time, distribute meaning and secure continuity. Whether the ember is leapt over in a Bohemian village or a Holika effigy cracks in the flame by an Indian field, the show of fire binds the living to a seasonal promise: that warmth will return, crops will grow, and people will gather again to mark the fragile, recurrent miracle of life.

Sources:

https://tinyurl.com/2dxhszlm

https://tinyurl.com/kgjg789

https://tinyurl.com/26yzb2b6

https://tinyurl.com/2y85xnhy

https://tinyurl.com/2ctmssyv

https://tinyurl.com/253c4mbu

https://tinyurl.com/vuuptdo

https://tinyurl.com/26sxu3g4

https://tinyurl.com/24wt6gww

https://tinyurl.com/27kmvq85