Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

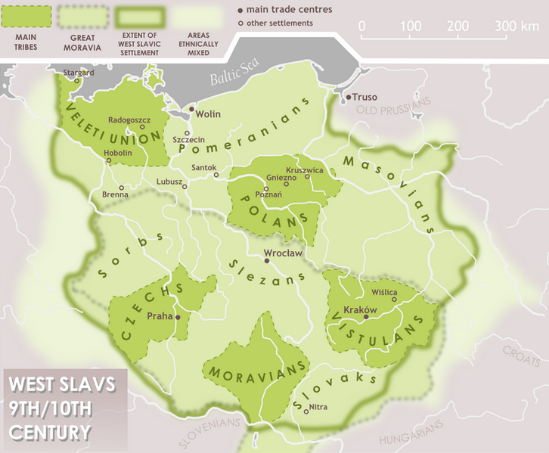

By the early centuries of the first millennium CE the lands that would later be called the Czech Republic, were continually reshaped, not by one sweeping conquest but by the gradual arrival of peoples, states and religions. Slavic groups, moving westward after the Migration Period, settled in the river valleys and uplands; out of these dispersed communities new states took shape. One of the clearest early indicators of political consolidation is the realm of Samo, a 7th-century state formed around 623 when a merchant-commander named Samo united different Slavic tribes and, briefly, held them together against Avars and Franks. Samo's realm, short-lived though it was, marks the first recorded attempt to turn Slavic identity into a political force in Central Europe.

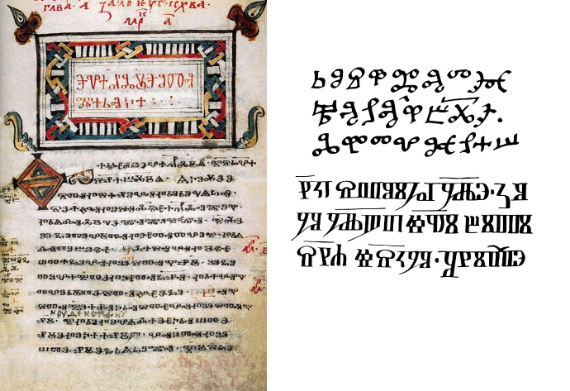

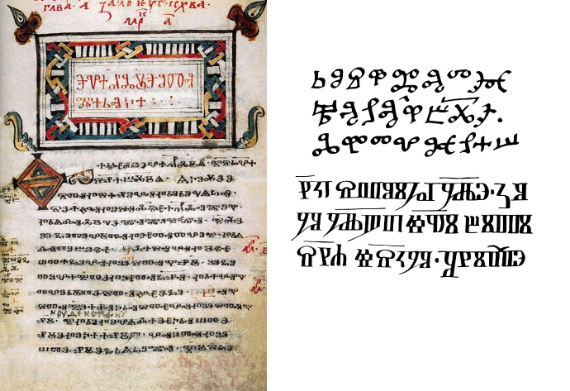

That early patchwork developed over the next two centuries into something more lasting. By the late 8th and 9th centuries the region centred on Moravia and western Slovakia came together into what historians have called Great Moravia, a state that, for a time, provided a centre of political authority and cultural exchange in Central Europe. In 863 an event of lasting cultural importance took place: the Greek brothers Cyril and Methodius arrived in Great Moravia as missionaries and translators. Their gift to the Slavic peoples was not merely a creed but a script: the Glagolitic alphabet and a liturgy in the local language that began to root Christianity in local tongues. In practical terms this meant that a Slavic cultural and religious language could now be fixed in writing, and the process of identity-building accelerated.

The story of Great Moravia is therefore a dual one: on the one hand a narrative of political formation and unstable frontiers; on the other, a tale of cultural consolidation. The state's decline in the face of Magyar attacks at the turn of the tenth century did not erase the changes it helped start. Capitals, bishoprics and newly literate elites survived in different forms, contributing to the rise of the Duchy of Bohemia and later medieval institutions that would reshape the map of the region. The Slavic peoples, by now recognized in broad linguistic and cultural groups — West, East and South Slavs — had acquired a set of political and church tools that would endure.

If Central Europe was thus assembling political foundations and a written Slavic culture, the other end of Eurasia, the Indian subcontinent, was also undergoing major changes that would affect trade routes and religious networks. The post-Gupta centuries (from the fifth century onward) saw the fragmentation of imperial authority and the rise of powerful regional dynasties across peninsular India. In place of a single dominant centre, a group of ruling houses, the Cheras, Cholas, Pandyas in the south, the Pallavas and later Chalukyas and Rashtrakutas in the Deccan, and a variety of courts in the Gangetic plain and eastern coasts, ruled territories and influenced commerce and culture. These states fostered temple building, supported learning, and oversaw active maritime trade that linked Indian ports to the Arabian Sea, the Persian Gulf and beyond.

Trade in this era was not limited to goods; it also carried ideas, religious traditions and clerical networks. The centuries after the Guptas witnessed flourishing internal trade and growing Indian Ocean exchange, as merchants, monks and craftsmen shaped a network of ties stretching from South India to Southeast Asia and westwards into the Persian world. Histories draw attention to the sustained activity of coastal ports and inland markets, and to the role of regional dynasties in supporting commercial stability. The result was an India that, while politically diverse, was closely connected, economically and intellectually, to the wider Eurasian world.

Between these two settings, Central Europe's river valleys and India's peninsular ports, there existed, in the imagination and in practical networks, lines of contact. Some were obvious: caravans and overland routes across the steppe and Anatolia, and maritime lanes across the Indian Ocean. Others were church-related: Christian communities outside Rome, notably those following the East Syrian (often called "Nestorian") rite, maintained church ties and missionary circuits that reached into India and across western Asia. What is clear is that India's commercial ties and the existence of non-Latin Christian communities created conduits through which ideas, texts and liturgical practices could travel.

Seen together, these separate histories show a Eurasian pattern of overlapping paths. In Central Europe the adoption of a liturgy in the local language and a script by Cyril and Methodius, recorded in contemporary accounts and later chronicles, anchored Slavic culture; in India the rise of regional dynasties and the intensification of maritime trade created multiple centres that nevertheless fed into common economic and religious currents. Both regions, though far apart geographically, were participants in a wider pattern: local states and local elites used the means at hand, such as script, liturgy, pilgrimage and commerce, to make their worlds easier to share and sustain.

For the historian this comparative glance matters because it challenges simplistic narratives that would treat regions as isolated. These centuries were marked as years of invention and translation: languages were written down, saints' lives circulated in newly accessible tongues, and commodities carried news of fashions and institutions. Material traces remain, such as chronicles of Samo and Great Moravia, the record of Cyril and Methodius' mission, and the temple inscriptions and port accounts of post-Gupta South and the Deccan, and they together suggest a Eurasia in which cultural and commercial currents blurred the distance between plains around Prague and the Indian shores.

Main Image: A page from the 11th‑century ‘Kiev Leaflets’ (Bulgarian), written in round Glagolitic; bottom: a South Slavic ‘Rhyming Gospel’ fragment in angular Glagolitic, shown together with the first page of the Gospel of Mark from the 10th–11th‑century Codex Zographensis, discovered at Zograf Monastery in 1843.

Sources:

https://tinyurl.com/27jknadr

https://tinyurl.com/22hlev2w

https://tinyurl.com/2a9mozzz

https://tinyurl.com/22hlev2w

https://tinyurl.com/2xhrx5lh

https://tinyurl.com/296pyksu

https://tinyurl.com/vuuptdo

https://tinyurl.com/2yx7xow7