Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Both the Bohemian basin and the Indian subcontinent had been woven into circuits of rule, ritual, and trade that hardened into institutions between the years 1000 and 1450. This era rewarded rulers who could convert conquest into predictable revenue, clerical literacy, and city foundations, a pattern that stamped durable signatures on Prague and Delhi alike. What follows pairs two geographies through the same window, tracing how dynasties made authority legible—on parchment and stone, in councils and bazaars—amid recurrent frontier pressures.

In the eleventh to thirteenth centuries, the Přemyslid dynasty consolidated Bohemia within the Holy Roman framework, building out ducal authority through aristocratic alliances, ecclesiastical patronage, and fortified seats that stabilized succession and taxation. The Přemyslids worked the advantages of imperial recognition while preserving the autonomy that made Prague’s court and clergy reliable partners in governance. This balance of outside sanction and inside consolidation gave Bohemia a political grammar resilient enough to navigate the later medieval century’s wars and successions.

The long twelfth‑ and early thirteenth‑century arc culminated in hereditary elevation, turning contingent ducal claims into more predictable royal rights and anchoring the realm’s estates in a firmer legal order. Hereditary status strengthened urban growth and castle administration, allowing rulers to standardize obligations and embed ecclesiastical institutions that mediated between crown and nobles. The result was a polity prepared to leverage imperial politics without dissolving its local scaffolding of offices, churches, and towns.

After 1300, the House of Luxembourg recentered Bohemia inside imperial strategy, with John of Bohemia’s chivalric reach and Charles IV’s administrative craftsmanship projecting Prague onto a continental stage. Luxembourg rule fused dynastic ambition with design: law codes, estates politics, and cultural endowments knit rule to urban life in ways that radiated across Central Europe. Under this program, Bohemia’s crown became both a regional keystone and an imperial lever, translating prestige into institutions that outlived individual reigns.

Prague’s fourteenth‑century ascent was the visible edge of Luxembourg governance, drawing clerics, jurists, and merchants into a civic fabric designed to serve both city and empire. Education, cult, and administration were not ornaments but load‑bearing elements of rule, binding fiscal practice to literate elites in cathedral, chancery, and guildhall. As the fifteenth century opened, these same networks became channels for reforming energies and contention, a sign of institutional vitality as much as strain.

On the Indian timeline, the thirteenth century registers the consolidation of Turkic‑Afghan power at Delhi, where the Sultanate systematized cavalry, revenue, and frontier defence across the North Indian Plain. Iltutmish and Balban embedded court and administrative norms that successors extended under shifting military and fiscal pressures. From this nucleus, Delhi’s authority reached both along riverine corridors and across dryland frontiers where resilience depended on bureaucratic repetition as much as on arms. The Khaljī dynasty drove hard into the Deccan and tightened market and fiscal controls to finance campaigns, revealing both the possibilities and stresses of rapid projection from a northern capital. These expeditions reframed the relationship between conquest, logistics, and revenue extraction, even as terrain and regional coalitions forced recalibration. What remained was an enlarged apparatus—costly, capable, and continually tested by distance, supply, and succession.

The Tughluqs magnified the scale of administration with bold monetary and territorial experiments whose side effects exposed the limits of centralized control. Attempts to reshape circulation and settlement patterns were legible in policy but uneven in practice, and opposition in frontier zones hardened into alternatives. By mid‑fourteenth century, strong regional actors were already learning to convert Delhi’s own methods to local ends.

In 1336, Vijayanagar rose on the Tungabhadra as a southern imperial center, drawing on temple‑court economies, cavalry reinforcements, and coastal trade to stabilize rule. As a Deccan counterweight, it rerouted resource flows and patronage, shaping a political geography in which the south could negotiate rather than merely receive northern pressures. Its institutions—courtly, fiscal, and cultic—translated territory into trust through ritual visibility and predictable dues, much as northern regimes had done in their sphere.

Timur’s 1398 assault sapped Delhi’s demographic and artisanal core, diminishing the city’s fiscal and symbolic centrality and accelerating regional assertion. The Sultanate endured in reduced form, but the center’s weakened credit licensed provincial ambitions and hardened new boundaries of possibility for post‑1398 politics. From this fracture emerged a late‑medieval landscape where Delhi remained a reference point but no longer the unchallenged clearinghouse of power.

Bohemia’s move from Přemyslid consolidation to Luxembourg centrality and India’s shift from regional polities to a Sultanate–Vijayanagar balance both hinged on translating arms into offices, estates, and cities. Authority that lasted was written into revenue routines, legal scripts, and liturgy as surely as into gates and walls, rendering loyalty verifiable and obligations calendared. In each theatre, the reliability of scribes, clergy, and guilds mattered as much as victory, because they converted events into systems.

In Bohemia, Luxembourg endowments and university life underscored Latin Christian learning and juridical culture, reinforcing the literacies that legitimated command. In India, Persianate court idioms and Vijayanagar’s temple‑court languages embedded authority in ritual performance and administrative prose that could travel across communities. These were not mere flourishes but conduits linking consent, taxation, and memory to doctrine and document.

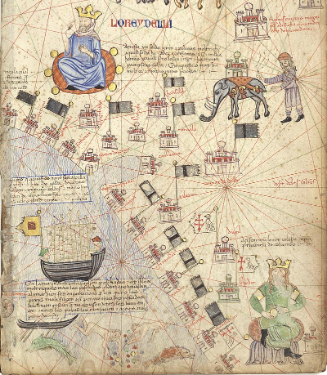

Prague’s fourteenth‑century magnetism tied imperial governance to merchant routes, making urban prosperity a daily referendum on royal design. Delhi’s prosperity—and later, Vijayanagar’s—likewise turned on the alignment of inland revenue with coastal exchange, stitching politics to market rhythms. Where roads, ports, and courts moved together, states found credit; where they drifted apart, frontiers sharpened.

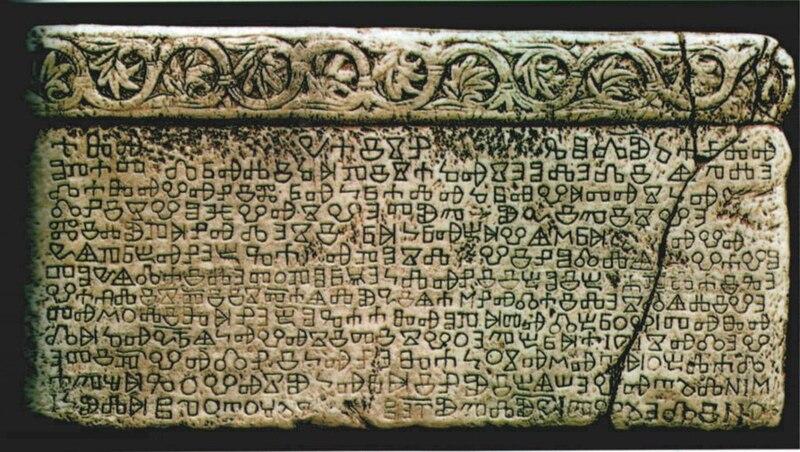

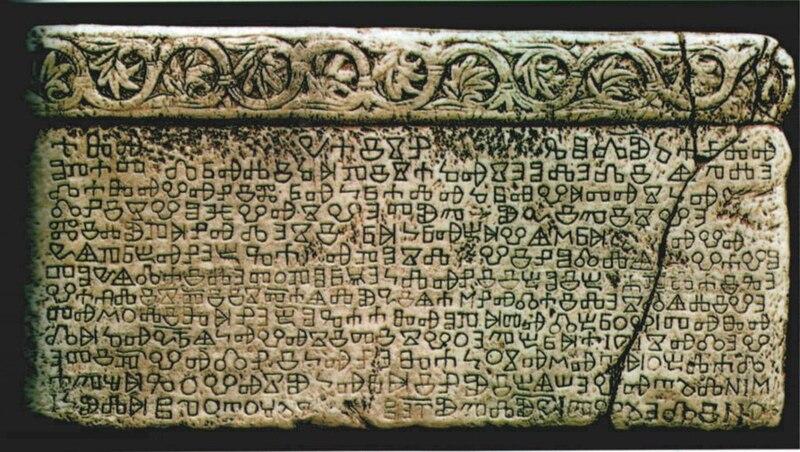

The Baška Tablet (Main Image), an 11th–12th‑century Glagolitic stone inscription from the Adriatic littoral, is a reminder that public literacy and political memory were already visible in stone across the high medieval Slav sphere. Its script and commemorative voice echo the wider Central European pattern in which written culture underwrote identity during the very centuries that saw Bohemia’s rise under the Přemyslids and Luxembourgs. A single slab, lettered for the ages, stands for a continental turn: when power learned to speak in durable texts and places.

From Prague’s estates to Delhi’s diwan, the years 1000–1450 forged regimes that measured themselves not only in battles won but in offices kept, dues collected, and schools and shrines maintained. The endurance of these arrangements—visible in city plans, in learned corporations, and in calendared taxes—explains why their traces still thread through modern political memory. What survives, finally, is a grammar of rule: institutions that made authority legible and thus believable, long after the noise of conquest faded.

Sources

https://tinyurl.com/2abzfyo8

https://tinyurl.com/22m6j87n

https://tinyurl.com/2c6hszv7

https://tinyurl.com/27fvy38m

https://tinyurl.com/2dzrs3gp

https://tinyurl.com/28gqla6w

https://tinyurl.com/22opwnb2

https://tinyurl.com/27dmp4c4

https://tinyurl.com/vuuptdo