Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

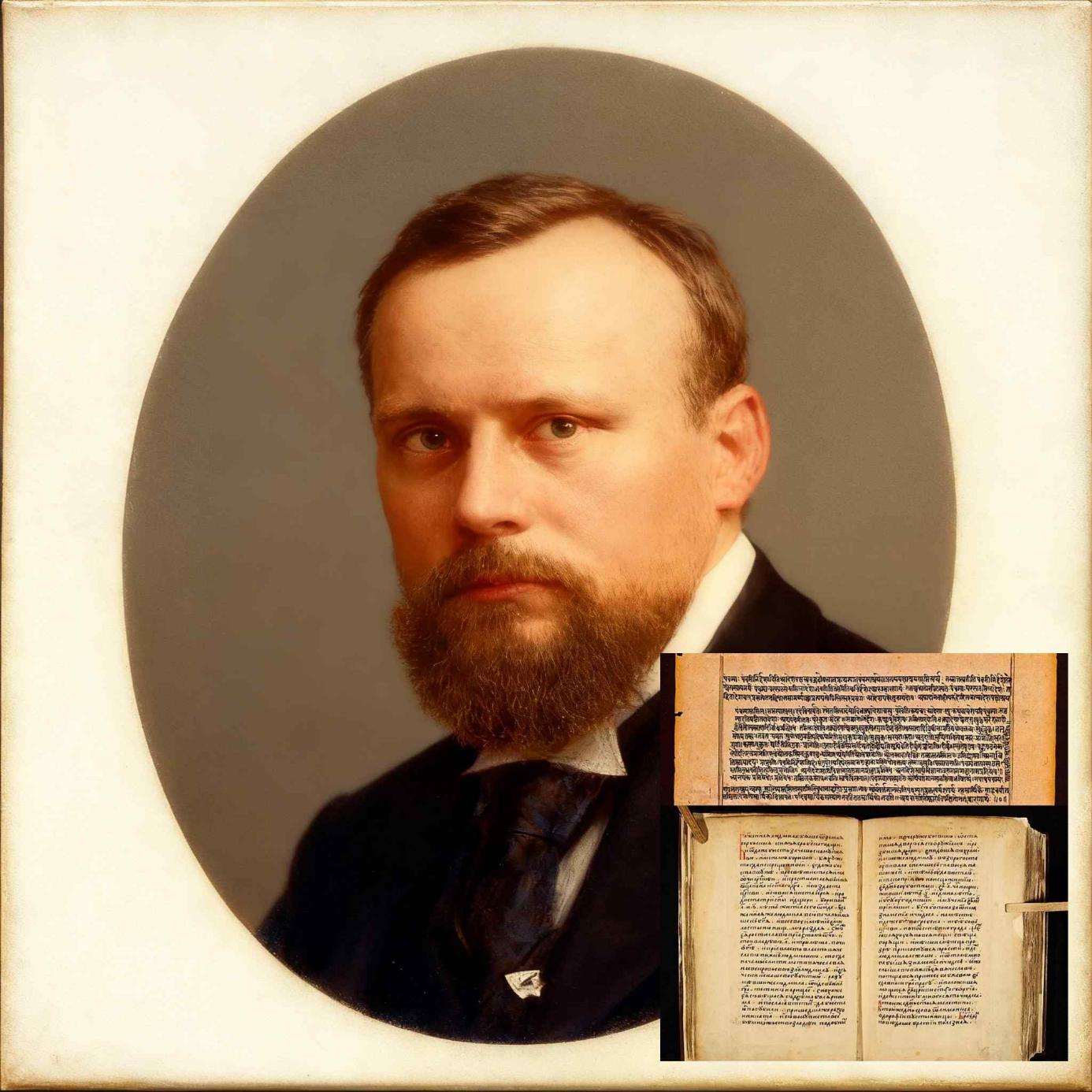

A single bookplate, a classroom list, a folded syllabus, the small things often tell the largest stories. Across Prague's university presses and a file in Delhi University, you can trace a scholarly and human relationship: Czech Republic scholars teaching Sanskrit and Hindi, Czech Republic students learning Devanāgarī, and Indian poets admired in Czech Republic salons. These modest traces—textbooks, course descriptions, radio interviews, and embassy notices—are the pieces through which we can read the long India–Czech Republic conversation.

Charles University in Prague is the anchor of this story. Since the nineteenth century, the Faculty of Arts has embraced Oriental studies, giving Sanskrit and later modern Indic languages a place in Czech Republic philology. Vincenc Pořízka, often named in institutional histories, established the first modern chair of Hindi at Charles University and compiled practical grammars and teaching materials that would shape Czech Republic's orientation to Hindi for the rest of the century. His disciple Vincenc Lesný and later Odolen Smékal continued the line: teaching, translating, and, in Smékal's singular case, composing poetry in Hindi even though he spent only brief intervals in India. That Czech philological tradition produced language teaching, many translations, and major Hindi–Czech dictionary projects. These acts—a chair being created, a grammar being published, or a translation being printed—built the foundation for cultural understanding.

A short vignette makes the point. In the 1950s Pořízka prepared a descriptive grammar and a parallel English–Czech - Hindi course (Hindština) that became the basic text for generations of Czech students. Decades later, Odolen Smékal—who translated Premchand and compiled modern Hindi poetry—read his own Hindi verses at Kavi Sammelans in India and later became the first Czech ambassador to New Delhi after 1990. A textbook and a diplomat's poems, these are the small items that show how language study turned into personal commitment and diplomatic service.

The Faculty of Arts' broad program helps explain this: it offers Hindi alongside Sanskrit and Bengali and has long been a hub for comparative Indo-European study. Charles University's philological culture was not incidental; it was institutional. The university produced specialists who combined classical training in Sanskrit with practical knowledge of modern Indo-Aryan languages and who made Prague a centre for Czech Indology in Europe.

This Czech scholarly fascination met practical language teaching in India itself. The University of Delhi, via its Department of Slavonic and Finno-Ugrian Studies, introduced Czech courses in the 1970s and now runs three levels of courses that use communicative, direct, and contrastive methods in English and Hindi. Delhi University's syllabus emphasizes conversation, workshops, film viewing, and technology-assisted learning; its goal is to prepare students to work or study in Czech Republic. In other words, the linguistic exchange runs both ways: Czechs learned Hindi in Prague; Indians learn Czech in Delhi.

Government and institutional support strengthened these people-to-people exchanges. The Embassy of India in Prague publicised scholarships and short-term Hindi courses for foreign students at Kendriya Hindi Sansthan, Agra, a scheme that included monthly stipends and subsidised travel for selected Czech applicants. Such scholarships are small instruments with large cultural consequences: a Czech student in Agra learning Devanāgarī becomes, upon return, a teacher, a translator, or an interpreter in cultural diplomacy. The scholarship form on an embassy website is thus a modest but decisive historical object.

If one looks for the specific cultural moment when Czech curiosity about India began to manifest itself, a set of twentieth-century encounters stand out, above all was Rabindranath Tagore's visits to Czechoslovakia in the 1920s. Tagore's readings and his friendship with Czech intellectuals like Vincenc Lesný left a mark in Czech music, literature and public imagination. Czech composers such as Leoš Janáček recorded impressions of Tagore's readings; a generation of Czech writers and scholars incorporated Indian poetics and philosophy into their own national revivalist projects. Tagore's presence, recorded in contemporary press and later radio reminiscences, is a reminder that literary friendship often precedes formal institutional ties.

Language itself has left faint but persistent footprints. Online dictionary categories of Czech terms derived from Sanskrit list lexical survivals, curiosities of etymology that testify to older scholarly interest in Indo-European languague roots and to occasional semantic borrowings. These lexical traces are small but telling: they do not define the national vocabulary, but they show a history of scholarly contact linking Prague's scholars to South Asia's ancient languages.

Pedagogy has also adapted to modern needs. Online and classroom resources aimed at Czech learners of Hindi emphasize contrasting pedagogy (leveraging English and Hindi), multimedia tools, and structured certificate-diploma learning sequences. Contemporary portals and departmental pages make clear that teaching Hindi to Czech speakers is now a small ecosystem: academic curricula, summer courses, and online tutorials combine to produce new cohorts of speakers and interpreters who sustain institutional links between the two countries. The methodical syllabus page at Delhi University documents exactly how such courses are organized, while modern language-learning platforms reflect current pragmatic needs for quick spoken competence.

Finally, there are the small human biographies that make theory practical. Dr Jan Filipský, a Czech Indologist, reflected in radio interviews on the cultural affinities that pull Czechs toward India: these include the fascination with Sanskrit, the sense that Czech national revivalists found parity with ancient Indian literary traditions, and the friendships between Czech translators and Indian writers. These interviews are not just memories; they are evidence of the relationships and emotions that sustain academic programs and student exchanges.

If one folds these documentary threads together a clear pattern emerges: language studies created lasting channels of mutual respect. Charles University produced grammar books, dictionaries, and generations of teachers. Delhi University's programs and Indian scholarships gave rise to more language practitioners. Embassy initiatives and cultural encounters, Tagore's readings, Smékal's translations, the Kendriya Hindi scholarships, made the relationship lived, not just formal and theoretical. The surviving artifacts, a textbook's prefatory note, a radio interview transcript, a scholarship circular, are the small archival objects by which historians reconstruct an entire intellectual and linguistic history.

Sources:

https://tinyurl.com/24gtnoe9

https://tinyurl.com/23xw6d2v

https://tinyurl.com/25kac82u

https://tinyurl.com/29r9kywl

https://tinyurl.com/29juycnp

https://tinyurl.com/2yhjdo2b

https://tinyurl.com/29agxymt

https://tinyurl.com/2acc7y2b