Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

A single program leaflet, folded at the crease and thumbed by many hands, can tell a longer story than a diplomatic communication. Open it and there are names of performers, dates of concerts, and the small institutional logos—the embassy, the cultural centre, the local promoter—that quietly map how culture travels. Across Prague and New Delhi, such leaflets and the concerts they list have stitched together a performing-arts relationship whose forms range from Bollywood choreography in community halls to puppetry from the Czech Republic staged for Indian children. These modest objects—photos in an events gallery, a festival program, a short academic paper on global dance—are the archival traces that reveal a friendship built through movement, music, and play.

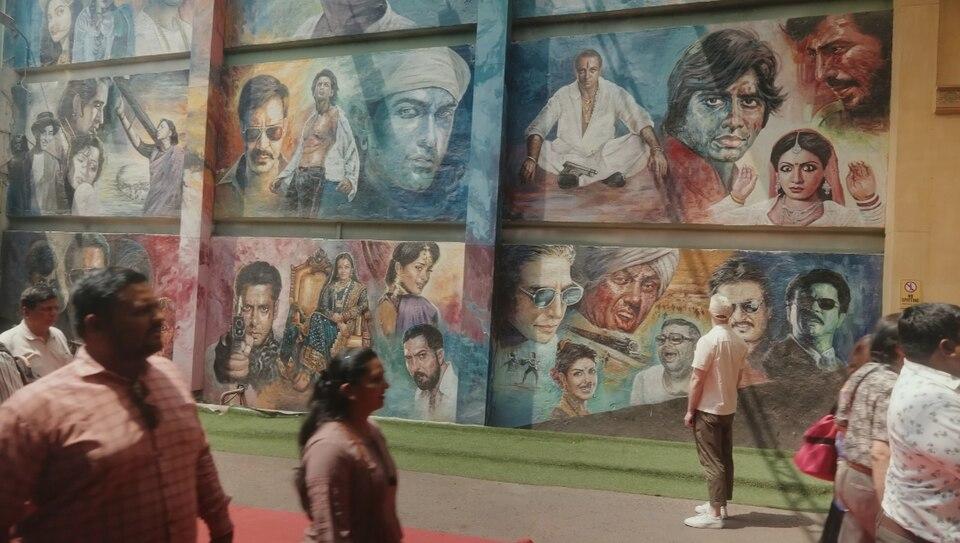

To begin with movement: Bollywood dance, once an inward-looking cinematic practice, has become a global and remarkably mobile idiom. Scholarly analysis describe the global spread of Bollywood dance—its spread as a mass, easily replicable form—which made it recognizable to audiences and performers far beyond India. Its hybrid choreography, which borrows from classical and folk movements as well as global pop forms, allows it to be both immediately accessible and endlessly adaptable; this is why dance workshops, film festival nights, and community shows in Prague and other towns in the Czech Republic often include Bollywood numbers on their programs. The academic portrait of Bollywood’s globalization explains the ease with which performers and amateur groups in the Czech Republic adopt and adapt film choreography for stage, charity nights, and festival events.

Film, of course, moves bodies and ideas together. The Prague Indian Film Festival has, in recent years, become a steady mainstay for audiences in the Czech Republic eager to encounter modern Indian cinema’s stories and aesthetics. Reports on the festival note its program of contemporary features and classics—a curated “taste of masala” for viewers in the Czech Republic—and the festival’s role in building an appreciative local audience for Indian film culture. Such festivals do more than show movies: they create meeting places for directors, critics, and students and fuel parallel events (talks, dance workshops, music nights) that deepen cultural engagement.

Official cultural diplomacy amplifies these grassroots ties. Embassy event pages and photo galleries record a steady calendar: “Bharat Week” concerts that bring Indian dance troupes and musicians to audiences in Prague, student recitals staged in partnership with local conservatories, and cross-cultural evenings where choirs from the Czech Republic sing in Hindi or Indian dancers perform in city theaters. These institutional initiatives matter because they provide the logistical framework—venues, travel support, repetition—that lets occasional encounters become enduring practices. The embassy’s events gallery, with its rows of images from concerts and collaborative evenings, reads like a sequence of postcards documenting cultural friendship in action.

Puppetry offers a particularly telling parallel. India’s living puppet traditions—from Rajasthani Kathputli to glove and shadow practices across the subcontinent—are catalogued by national cultural agencies as distinct forms with ritual, social, and narrative functions. The Centre for Cultural Resources and Training (CCRT) lists the many puppet forms—their materials, regional styles, and performance contexts—and thus demonstrates how puppetry is a repository of folk narrative, devotional enactment, and popular theater. The Czech Republic also has a distinguished puppetry tradition; the craft and repertory of puppetry from the Czech Republic have been shared internationally through touring companies and workshops. That both cultures treasure theatrical miniature forms creates an easy terrain for exchange: puppet workshops, joint residencies, and children’s theater festivals where Kathputli and marionette techniques from the Czech Republic are shown side by side.

A concrete vignette makes this relation visible. Imagine a packed hall in Prague during a “Bharat Week” night: an Indian kathak troupe dances, then a short puppet sequence enacts a folk tale, and finally a local ensemble from the Czech Republic sings a folk song from the Czech Republic. The program not only presents differences—it fosters mutuality. The audience claps for rhythm and story; the choreography’s footwork is discussed later in a workshop; the puppeteers exchange notes on rod lengths and joint mechanisms. Such evenings turn technical detail (how to align a rod or shape a kathak ghunghroo beat) into shared know-how.

Beyond staged events, pedagogy is a second strand binding the two scenes. Dance and film workshops attached to festivals give students in the Czech Republic hands-on contact with Indian forms; in turn, Indian cultural centres and visiting performers have run short master classes in Prague conservatories and municipal cultural houses. The pedagogical logic is simple but consequential: a single workshop can produce teachers who, over years, run classes in Indian dance in towns in the Czech Republic; film panel discussions can inspire local filmmakers to stage cross-cultural projects. These are the incremental, human-scale processes that turn occasional tours into lasting affinities. The embassy gallery’s repeated images of workshops and master classes show this gradual accumulation.

The exchange is also social and affective. Popular culture and celebrity stories—the human tales of artists who move between continents, or of local performers in the Czech Republic who adopt Bollywood styles—shape public imagination. Academic work on globalization of dance underscores how dance forms that carry less ideological content (popular film dances) travel quickly because they adapt easily; they provide a joyful, low-barrier entry point to cross-cultural participation. In practical terms this means that a college dance club in Prague can stage a Bollywood routine and fill a theater without long debates about authenticity; the same ease allows serious classical culture collaborations to coexist with pop‑inflected nights.

Finally, the performing-arts bridge bears small but durable economic and institutional fruit. Festivals create markets for costumes, recordings, and choreography rights; puppet workshops sustain craftspeople and keep alive woodworking and textile skills; film screenings foster subtitling, distribution, and festival networks that benefit both small distributors in the Czech Republic and Indian filmmakers seeking European circuits. In short, cultural exchange builds lasting cultural infrastructure: it supports livelihoods as well as fellowship. The modest event pages and festival reports, when read together, show how art produces both joy and jobs.

Main Image: "Dancing on a Shore", By Norwegian artist Edvard Munch in 1900, housed in the National Gallery, Prague

Sources:

https://tinyurl.com/25hgocdx

https://tinyurl.com/24utgver

https://tinyurl.com/29n7f62p

https://tinyurl.com/27f93e34

https://tinyurl.com/22dh8dt5

https://tinyurl.com/28c2lgdf

https://tinyurl.com/yuuktce2