Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

By the first decades of the twentieth century, artistic itineraries had become another way in which distant worlds narrated one another. Painters from the Czech Republic traveled to Ceylon and India with the same mixture of idealism and inexperience that marked many an expatriate venture (they often set out without money or knowledge of English language), and the works they brought back—oils, linocuts, illustrated memoirs—created durable threads between Prague and Calcutta, Bombay and Santiniketan. These threads, visible in exhibition catalogs, museum accession lists, and the occasional auction note, reveal a clear reciprocity: Indian modernism entered institutional collections in the Czech Republic even as painters from the Czech Republic absorbed Indian landscapes, people, and print traditions into their own visual vocabularies. This reciprocity appears in three overlapping registers: through the painter-travelers Jaroslav Hněvkovský and Otakar Nejedlý (their journeys, hardships, and exhibitions), on the one hand, and the international circulation of politically charged prints by India artist Chittaprosad Bhattacharya (and his Prague friendships) on the other hand, and the way institutions in the Czech Republic, above all National Gallery Prague, gathered works by major Indian modernists into a visible, if modest, canon.

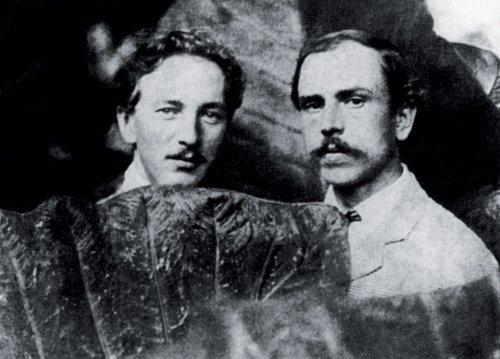

The case of Jaroslav Hněvkovský is emblematic. Known in the Czech Republic as the “Painter of India” and sometimes celebrated as a “Slavic Gauguin,” Hněvkovský’s India years are described as the period when his subject matter and reputation crystallized. An Untitled, 1911 produced, 66 x 76.2 cm oil painting, depicting a Jungle Scene in Kerala, place Hněvkovský within two complementary stories: a romantic artist-traveller who spent several seasons painting in the subcontinent, and secondly as an exhibitor whose Indian work made a European circuit. There is a small, important discrepancy in the accounts over the precise year of the first voyage—some date the journey to 1909, others to 1911—but consensus is that a protracted Indian stay produced a body of jungle and city views that later circulated in London and Prague. Accounts also refer to his meeting with Rabindranath Tagore, who invited him to Santiniketan.

The artist Otakar Nejedlý’s trajectory runs alongside Hněvkovský’s..Nejedlý—born in 1883 and later a professor at Prague’s Academy—accompanied Hněvkovský to Ceylon and India; his memoirs and biographical entries narrate the voyage’s hardships (poverty, illness, malaria) and the pragmatic reasons that compelled an early return to Europe (Nejedlý returned in 1911 while Hněvkovský stayed on). Nejedlý’s published recollections, a book of impressions from Ceylon and India appeared in 1916, and his later role as an influential teacher indicate how experience abroad fed back into artistic life in the Czech Republic: travel produced both pictures and pedagogy. Visual traces of these survive in reproductions and image captions that consolidate the painter’s reputation across museums and online archives.

A second strand of exchange was more political: manifested in the circulation of prints and in the solidarity it generated between the 2 countries. Chittaprosad Bhattacharya—the Bengali artist whose representation of the famine of 1943–44 and the subsequent production of linocuts testified to an engaged, left-leaning graphic practice— and it thereby sustained a long association with Prague and its people. Czechoslovak networks (institutions, journals, and individuals) took up his work: linocuts by Chittaprosad entered National Gallery of Prague in the early 1960s; his works and illustrations circulated in the journal Nový Orient/New Orient Bimonthly; and personal friendships, notably with František Salaba (assistant to the Czechoslovak trade commissioner in Bombay, 1954–57), led to practical support. Salaba not only organized exhibitions of toys and puppets in Bombay but also gave Chittaprosad puppets and a stage—material aid that enabled the artist’s Khelaghar puppet theater for children in Andheri, Mumbai. These are the kinds of biographical details that show cultural exchange as durable, embedded, and occasionally asymmetrical: Prague supplied platforms, journals, and friends; Chittaprosad contributed images, scripts, and political urgency that resonated with socialist cultural networks.

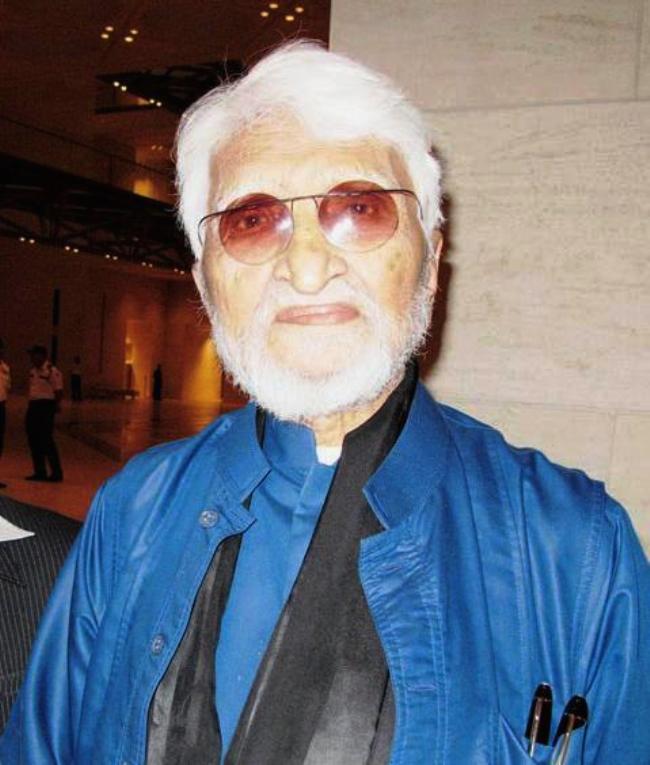

The Prague side of the exchange was institutional as well as personal. National Gallery Prague’s Department of Oriental Art (established by decree in 1951) now manages a collection numbering in the tens of thousands, and within its South and Southeast Asian holdings the museum lists 20th-century Indian prints and paintings, including names familiar to any history of modern Indian art: M. F. Husain, Ram Kumar, Biren De, and Chittaprosad. This institutional fact—that these artists appear on the Gallery’s lists—matters for how national canons are imagined; it suggests that the Czech Republic’s gallery acquisition policy, from the mid-20th century onward, actively incorporated modern South Asian art into its narrative of global modernisms. The Gallery’s Asian collection thus serves as an archival hub connecting Prague to multiple modernisms: the woodcut and linocut circulations, the pedagogical legacies originating in Bombay’s art schools, and the transnational solidarities that animated postcolonial cultural exchange.

Finally, a brief word on context: European academic realism and the institutional infrastructures that brought oil painting and studio pedagogy to Indian art schools also shaped what foreign visitors encountered. Overviews of the academic tradition emphasize the role of schools such as the Sir J. J. School of Art and the wider diffusion of European techniques in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; these pedagogical currents formed the background against which both Indian modernists and visiting Europeans worked, taught, and displayed their works. That context helps to explain why a Santiniketan invitation—Tagore’s appeal to Hněvkovský to teach—would have seemed sensible to both parties: one side sought new forms and expressive vocabularies; the other had technical mastery to share.

Taken together, these documentary strands suggest a pattern that is modest but unmistakable: painters who left Prague for the subcontinent returned with canvases, memoirs, and professional reputations; Indian printmakers and political artists found in Prague's journals, curators, and friends a receptive and helpful audience; and cultural institutions in the Czech Republic, over decades, collected works by Indian modernists and socially committed artists, thus stabilizing a cross-regional archive of modern art. The exchanges were not symmetrical, and they were not merely aesthetic: they were also pedagogical, and at times ideological. Yet from the jungle scenes of Kerala to the linocuts of a famine-era Bengal, from a puppet stage in Andheri to a gallery accession list in Prague, visual art forged concrete bonds across an ocean and across cultural differences—bonds that survive in canvas, catalogue, and correspondence.

Main Image: Inside Sternbersky Palace, Praha

Sources:

https://tinyurl.com/2c5uqxom

https://tinyurl.com/249gg6x4

https://tinyurl.com/29goyfou

https://tinyurl.com/222oy8nr

https://tinyurl.com/y7h852cd

https://tinyurl.com/2yhcqqzj

https://tinyurl.com/2cqnfmvm

https://tinyurl.com/28hvd5dw