Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

By its nature, yoga resists any single story. It is at once practice, philosophy and an array of institutional lineages — a living archive of texts, teachers and places that stretches from the riverbanks of ancient India to modern studio rooms in Prague. To follow that archive is to notice two parallel movements: Inward, as the long spiritual path toward “Samadhi” (as a discipline of breath, mind and ethical living); and outward, as twentieth- and twenty-first-century expansion of teachers, schools and civic initiatives that have carried those practices into global civic life. In this article we will see how these two movements meet: in institutions (the Bihar School of Yoga; Yoga in Daily Life), in global networks (the European Union of Yoga), and in local practice (retreats in Slavonice; Sahaja Yoga centres across Czech regions).

Any careful telling must begin in India, where yoga’s spiritual grammar took shape. Travel accounts and contemporary guides remind us that what many Western studios present as “yoga” — an asana class, sometimes stripped of ritual — is only one limb of a much older system whose aims were ethical and spiritual as much as physical. Even now in India, the emphasis remains on spiritual discipline, on meditation and on scriptural study (the Yoga Sūtras, the Bhagavad Gītā) rather than merely on exercise. The asana, in this telling, is a preparatory technology to steady the body for inner upliftment. This is not a modern claim alone: commentators and modern teachers alike observe that the practice’s vocabulary (prāṇāyāma, dhyāna, the yamas and niyamas) is contiguous with Hindu philosophical categories, even as modern practice is plural and variegated.

Yet that proximity to Hindu thought does not reduce yoga to a single institutional religion. Contemporary expositions by teachers emphasise nuance: yoga predates many world religions, it carries moral precepts and devotional practices in some lineages, and it can be taught as a largely secular technique in others. In short, yoga appears both as a spiritual technology embedded in Indian religio-philosophical traditions, and as a set of practices that can be adapted — sometimes deliberately secularised — for cross-cultural teaching (a point that underwrites much of the European reception). This paradox — sacred origin, plural contemporary forms — is one that institutions on both sides of the movement have learned to manage.

Institutional anchors make that management visible. The Bihar School of Yoga (Munger, Bihar) is repeatedly listed in Indian institutional rosters and histories as a mid-twentieth-century attempt to systematise a holistic approach — a centre where asana, breath-work, meditation and daily discipline are taught as a joint program (the school is routinely cited in institutional directories as a prominent founding node of modern institutional yoga). Likewise, the organisation Yoga in Daily Life sets out an explicit spiritual lineage and global network: its pages describe an ashram-based heritage, a founder (Paramhans Swami Maheshwarananda) and an international fellowship whose aims include cultural appreciation and religious respect. These are not mere labels: they are functioning organisations that host retreats, charitable activities and centres “around the globe,” and they therefore exemplify the way Indian institutions have shaped the contemporary cultural life of yoga beyond India’s borders.

Europe’s reception of yoga has its own story, one both scholarly and organisational. Academic overviews (a recent Brill chapter on “Yoga in Europe”) have traced how yoga moved from exotic practice to European public culture, while federations such as the European Union of Yoga (founded in 1971) irrigate the continent with a network of teachers, national federations and an annual multilingual congress at Zinal where invited Indian teachers regularly appear. The EUY’s institutional practice — a formal teacher-training syllabus, multilateral membership across national federations and a long history of annual congresses — illustrates the organizational weight behind yoga’s spread in Europe and the way European circuits have sometimes adopted a secularised, training-focused form of yoga while still inviting Indian teachers to speak and teach. (The Zinal congress, in particular, is repeatedly cited as a meeting place for cross-cultural exchange.)

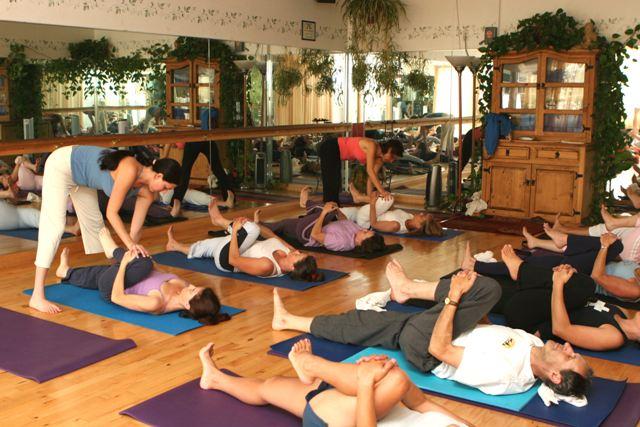

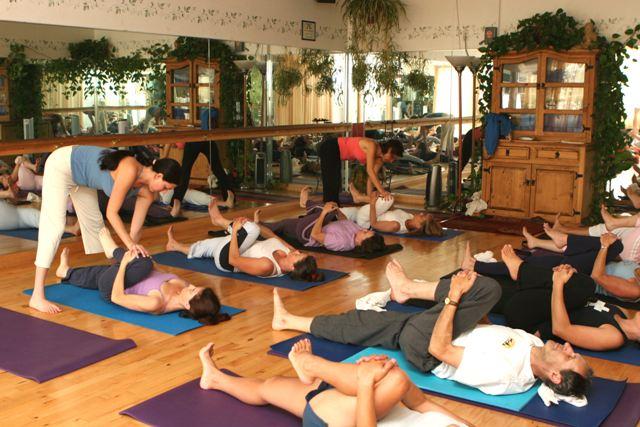

How do these macro-movements show up at street level in the Czech Republic? The evidence assembled here is concrete rather than rhetorical. YogaOmline’s Czech page records Indian teachers and retreats held in small Czech towns (Slavonice is named as a recurring retreat venue and an Indian teacher, Ashwani Bhanot, is mentioned as a visiting instructor), indicating the active flow of teachers and programs between India and Czech localities. Directory listings aimed at expatriates in Prague name specific centres (for example, Yogaspace near Anděl) and mindfulness teachers advertising bilingual classes; Sahaja Yoga’s centre listings show an organised presence across several Czech regions; and a mix of local and international organisations advertise workshops, retreats and teacher trainings. These local traces — a retreat notice, a Prague studio listing, a network map of meditation centres — highlight how yoga’s spiritual and physical practices have been woven into Czech civic life, sometimes as secular fitness, sometimes as devotional practice, and often as a hybrid that foregrounds wellness and cultural exchange.

What unites these varied threads — ancient scripture and modern studio, ashram and Zinal congress, Bihar School and a Slavonice retreat — is a shared grammar of encountering difference with respect. Indian institutions offer lineage and a pedagogical frame; European federations provide curricula, certification and meeting places; local Czech groups translate both into practice rooms and community centres. The result is not a flattening of meaning but a plural archive: yoga remains, for many, an explicitly spiritual discipline bound to Hindu philosophical vocabularies; for others it is a tool for mental and physical health; and for many more it is both, learned with an eye to historical depth and local adaptation.

If there is a modest moral to be drawn from this book-like geography, it is that cultural exchange — even in the realm of embodied practice — leaves traceable institutional footprints. A named school in Bihar appears in institutional directories; European union holds a multilingual congress; a Czech town hosts an Indian teacher’s retreat; and an international ashram lists centres “around the globe.” These are not abstract connections but archived practices: programmes, registrations, retreat notices and bulletin-board listings that together show yoga as both a sacred Indian heritage and a universal practice that can foster wellness, respect and meaningful cultural exchange.

Sources:

https://tinyurl.com/2djymvej

https://tinyurl.com/2am4a333

https://tinyurl.com/2yftvnf5

https://tinyurl.com/2cgb2eq6

https://tinyurl.com/23torlwf

https://tinyurl.com/2436ye3o

https://tinyurl.com/292hlb7k

https://tinyurl.com/2258ca4e

https://tinyurl.com/2xqzz3pt

https://tinyurl.com/2ad53dcv

https://tinyurl.com/29tfy3ka

https://tinyurl.com/24cyg3jx

https://tinyurl.com/2cgrlhqx