Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

Timelines 10

Man and his Senses 10

Man and his Inventions 10

Geography 10

Fauna 10

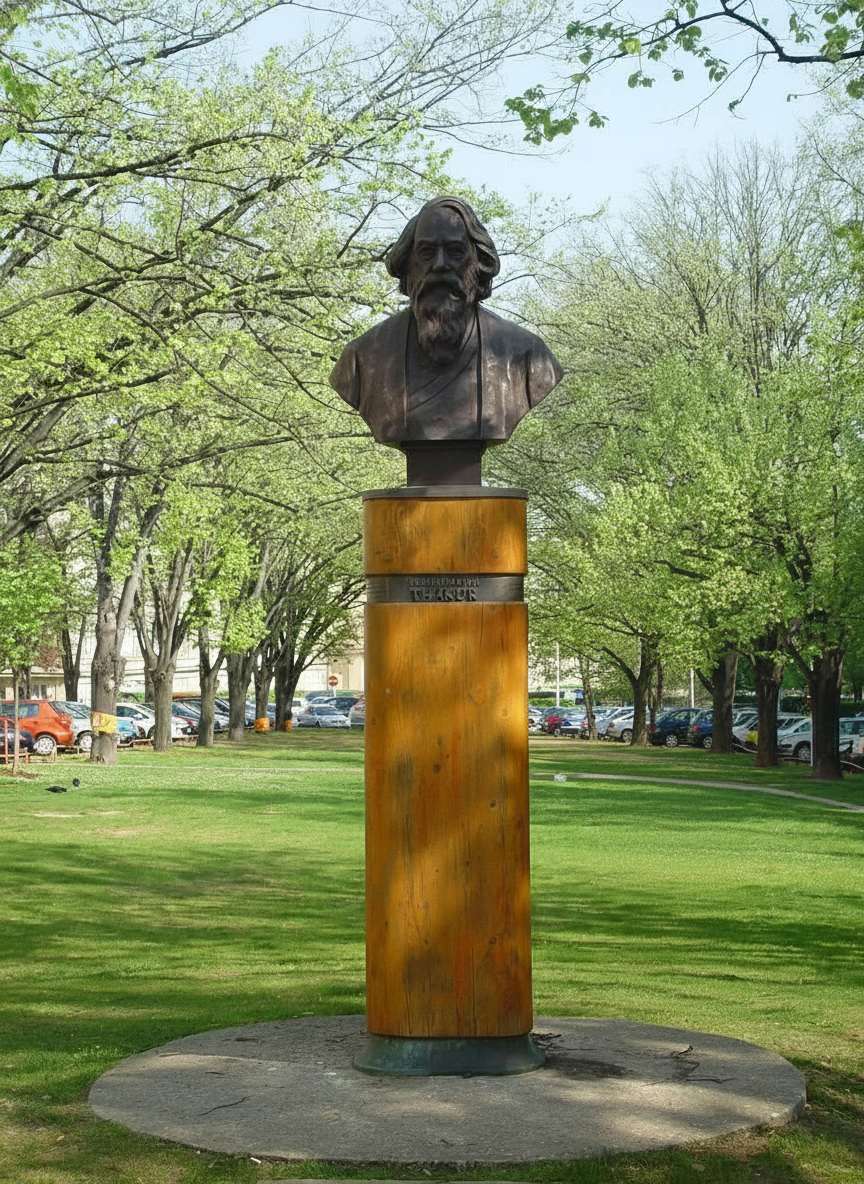

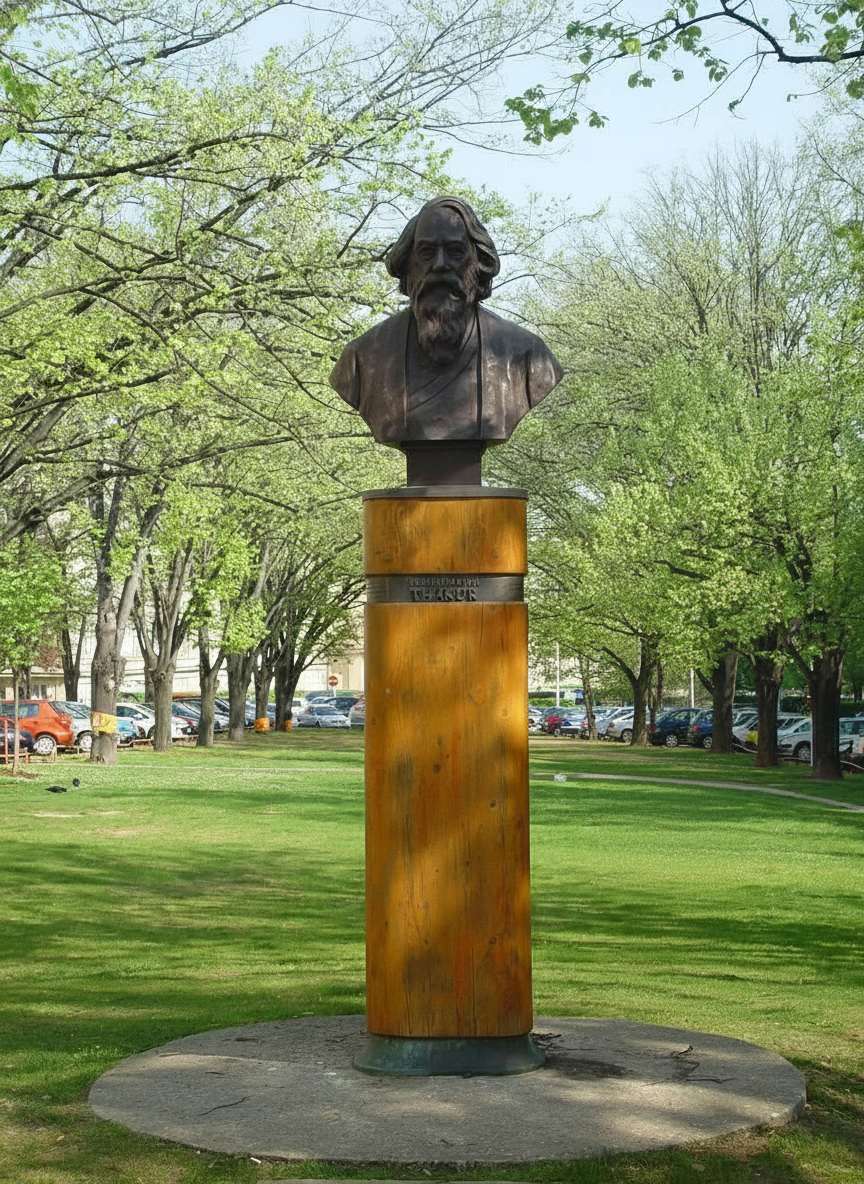

By temperament and practice, Rabindranath Tagore was a bridge-builder: not the brittle, parliamentary kind of diplomat but a public intellectual whose poems, plays and ideas traveled as petitions for humane education and cross-cultural sympathy. In Prague his presence took visible form — a street named Thákurova, a bronze bust, two visits in the 1920s, and a string of translations and performances — and, less visibly, it left a philosophical trace in Czech letters and pedagogy. Numerous radio features, archival reportage and scholarly essays on Tagore’s educational thought — show how a poet from Santiniketan became a recurring interlocutor for Czech scholars (and, through them, Czech audiences) during an era marked by political turbulence and a hunger for humane alternatives to dogma.

Tagore’s visits to Prague were short but consequential. He came in 1921 (a brief lecture tour) and again in 1928; the latter visit saw two of his plays staged at the National Theatre, and in the German theatre. These theatricals brought his dramatic voice into Czech public life and prompted musical responses (Leoš Janáček, for example, set Tagore’s words into choral music). These concrete cultural events — lectures in the Lucerna ballroom, plays on the National Theatre stage — are the kind of archival waypoints that explain why Tagore’s name persisted in Czech cultural memory.

If one asks why Tagore mattered to Czech intellectuals, the answer given repeatedly in the Czech sources is humanism in multiple registers: literary humanism (the lyric optimism of Gitanjali), pedagogical humanism (an education centred on freedom, nature and creative activity), and political humanism (a public stance against fascism and for international solidarity). Czech scholars point to the affinity felt since the nineteenth-century national revival — an early interest in Sanskrit and a romantic sympathy for colonised nations — and to institutional friendships that turned into personal ones (Vincenc Lesný, a founder of Indology at Charles University, became a close friend and interlocutor; Dušan Zbavitel later became the country’s foremost Tagore scholar and translator). These details are important: they make Tagore’s Prague presence less an exotic import and more a reciprocal intellectual conversation.

Tagore’s educational thought provides another archival anchor for Czech admiration. His project at Shantiniketan and its later institutionalisation in Visva-Bharati embodied a pedagogy that fused naturalism, idealism and internationalism. It included methodologies such as learning in the open air, instruction in the mother-tongue, arts integrated into the curriculum, and a method that privileged activity, dialogue and self-discipline over rote memorisation. Contemporary Indian academic surveys of Tagore’s pedagogy emphasise these features — self-realisation as an aim, the role of the teacher as a guide not taskmaster, and a curriculum that tied local culture to global exchange — and they explicitly cast Visva-Bharati as a meeting place for scholars from many lands. It is precisely this blend of the local and the universal that Czech academics and cultural figures found congenial.

Tagore’s humanism also carried political weight. In the 1930s, he publicly condemned fascism and supported democratic solidarity with Czechoslovakia; his gestures were read and re-read on both sides, thereby cementing his image in Czech memory as an “ambassador of peace and understanding.” That moral voice mattered greatly at a time when Prague’s civic life was being thrown apart by extremism. Tagore’s public interventions, and Czech responses (Karel Čapek’s broadcast greeting in 1937, for example), became part of a shared archive of resistance to tyranny. These episodes — public letters, broadcasts and gestures of solidarity — are not mere ornaments in the story but evidence of how ethical ideas were converted into civic practice.

Two institutional mechanisms explain how ideas moved across this bridge. First was the personal and scholarly network, such as that with Vincenc Lesný, who was not only an early Czech Indologist, but he was also invited as a teacher at Visva-Bharati, and it was Lesný’s friendship that helped in procuring Tagore’s Prague invitations and getting Czech translations done of his work. Second was the steady work of the translators and publishers — Dušan Zbavitel’s translations and the republication of Tagore's work in the 1950s — kept Tagore’s voice audible even through ideological shifts in postwar Czechoslovakia. Taken together, these mechanisms produced a many pronged reception: Czech composers set Tagore’s lines to music; Czech theatres staged his plays; and Czech scholarship debated his pedagogy and philosophy.

For readers interested in what Tagore taught by example, his institutional footprints are instructive. His creations, Shantiniketan and Visva-Bharati, embody a pedagogy of openness — to include learning through nature and craft, instruction in the mother tongue, and an insistence that education serve the entire life of a student, rather than being treated merely as a preparation for exams. These features have been well documented in Indian institutional surveys and contemporary essays on Tagore’s educational theory. These practical commitments explain why Czech academicians, themselves interested in humane education and comparative philology, were attracted to and stimulated by Tagore’s work.

Finally, a short note about intellectual kinship: several of the available essays that situate Tagore in a broader frame connect his humanism to other modern Indian figures. Scholarly overviews identify Tagore and Gandhi as modern humanists — differing in practice but overlapping in a commitment to human dignity and anti-colonial ethics — and such comparisons help place Tagore within a wider modern Indian formation that resonated with Czech hopes for humane politics and pedagogy.

Regarding Tagore's connection with, and visits to the Czech Republic, what survives most prominently in the Prague archives is not merely a catalogue of events, but a bouquet of civic learning: a poet’s lectures, a friend-scholar’s translations, a composer’s choral settings, theatrical stagings, and a stream of public letters and broadcasts that together demonstrate how ideas travel. Tagore’s legacy in this dialogue is double: in India he left an institutional model (Visva-Bharati, Shantiniketan) that insisted on pedagogy as a form of freedom; in Prague he left an ethical script that writers, musicians and scholars could read as an alternative to authoritarian certainties. That two-way conversation — pedagogical, musical, theatrical and political — is the historical fact the sources keep returning us to.

Sources:

https://tinyurl.com/25kac82u

https://tinyurl.com/29juycnp

https://tinyurl.com/297exbpl

https://tinyurl.com/23vgan6u

https://tinyurl.com/24dgxebt

https://tinyurl.com/2cml9tvr

https://tinyurl.com/mr3k2zuk

Main Image: Thakurova Street in Prague is named after Rabindranath Tagore